ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

48 Baltimore Checkerspot Euphydryas phaeton (Drury, 1773)

Host Plants and Habitat Relative Abundance Today State Distribution and Locations Broods and Flight Time Outlook

The glorious Baltimore Checkerspot is one of four lovely butterflies which grace our wet meadows in summer. It is the most well-known and often-seen; the others, Harris’ Checkerspot, Silver-bordered Fritillary, and Bronze Copper are all a bit harder to find, and their status is less secure. All four depend on the conservation and proper management of moist meadows adjacent to bogs, streams, and ponds.

In the 19th century Scudder considered the Baltimore to be “abundant” throughout New England, although collectors often thought it rare -- probably because they didn't venture into wet areas: “It occurs only in bogs or moist and shady meadows of small extent seldom frequented by the aurelian, and is often so limited in its range as scarcely to be seen one hundred yards from a spot where it swarms..... Indeed one might collect butterflies for years and consider phaeton the rarest of the tribe, while multitudes sport in security within a few rods of the beaten track (1889: 695-6).”

Newton naturalist Charles Maynard found Baltimore Checkerspot to be very local in the Boston area. “I know of only two or three meadows in which it occurs. These are those peculiar localities under laid with peat, which are not uncommon throughout New England. One of these places is in Belmont, occupying an area of about two acres, one side of which is bordered by woodland, and I never saw this species outside of this restricted section, although they are quite common or even abundant there, during the short season of their flight (Maynard 1886).” Could anyone find a colony of Baltimores in the dense suburb of Belmont today?

Photo: Mill Pond Recreation Area, West Newbury, MA, T. Whelan, July 7, 2006

A. H. Clark reports on another now-extirpated colony in the Boston suburbs: “In the latter part of June, 1897, while crossing a boggy meadow in Newtonville, Massachusetts, bounded on the north by Otis Street and on the east by Lowell Avenue, I found this species, previously unknown in that locality, very abundant. Returning immediately with my net, I captured about thirty specimens.... So far as I know no butterflies of this species have ever been taken in this locality since (Clark, 1913).”

Thaddeus W. Harris had the earliest known Massachusetts specimens in his 1820-50 collection: 3 from Salem, June 1, 1827, Dr. Pickering. Harris also had specimens from Waltham and Nonantum (Newton) (Index; Harris Collection, MCZ). F. H. Sprague took an astounding and probably quite unnecessary number of specimens in Wollaston (Quincy) in 1878: 6 on June 19, 42 on June 20, another 32 on June 21, and five more on June 24. There are also MCZ specimens from Malden (6/15/1883, F. H. Sprague), Dedham Purgatory Swamp (6/13/1895, W. Faxon), Belmont (6/21/1896, C. Bullard), "Fells" ( n.d., Scudder Collection), Wellesley (1896, Denton mount), Wareham (6/20/1900, no coll.), and Weston (6/19/1919, C. J. Paine), as well as Milton (6/11/1915, no coll., BU), and Stoneham (7/2/1928, C. V. Blackburn, Furman U.) A specimen from Taunton, Hockamok Swamp, (6/29/1936, C. L. Remington), is at Yale. In 1941, it was found on Martha's Vineyard (see below).

In central and western Massachusetts at the turn of the century, Baltimore Checkerspot was collected in Belchertown (8 July, 1878, referenced in Sprague 1879), Framingham (6/19/1904, no coll., BU), Princeton (6/17, no year, L. W. Swett, BU), and Mt. Tom (6/14/1905, no coll., BU). Scudder (1889: 695) also mentions Springfield and Amherst. By 1934, Farquhar's review of New England specimens adds the eastern locations of Marblehead, Canton and Reading to the list, but no new central or western locations. The earliest far western specimens appear to be those at Yale Peabody Museum: Richmond (7/4/1962, O. R. Taylor), Mt. Greylock (7/15/1964, no coll.), and Heath (7/1981, S. D. Coe).

It seems likely that Baltimore Checkerspot was in fact widely distributed across the state during the late 19th and the 20th centuries. Wet meadow habitat was likely opened up during the period of initial forest clearing in Massachusetts (Table 1). But much habitat was also lost as a result of the later more intensive agricultural development, which involved not just grazing or haying of wet meadows, but also plowing, ditching and draining them. Then, after about 1900, there was also widespread loss of natural wetlands and farms to road-building and urban and suburban development. From these causes Baltimore Checkerspot may have decreased between 1900 and 1980, before its adoption of plantain as a new host plant (Table 2).

Baltimore Checkerspot’s traditional native host plant in the northeast is white turtlehead (Chelone glabra), and it continues to use this plant where good stands are available. In 1978, it was first noticed ovipositing on the widespread introduced weed, lance-leaved plantain (Plantago lanceolata) in two fields in upstate New York (Stamp 1979). Later, caterpillars of all instars were found on this plant, and Baltimore Checkerspot is thus one of the many butterfly species to have adopted new non-native larval hosts (Table 3: Switchers). Some studies suggest that larvae do not thrive as well on plantain as on white turtlehead, and more studies are underway, but in the years reviewed here the switch to a new host plant has led to population increases in Massachusetts.

In Massachusetts, colonies of Baltimore Checkerspot were first discovered feeding on plantain in South Dartmouth in 1987 by Mark Mello and in West Bridgewater in 1989 by Don Adams (LSSS, 1987, 1989). In Dartmouth, Baltimore caterpillars were found in a residential lawn near the Lloyd Center for the Environment, feeding on plantain. Later, females were seen laying eggs on the plantain. As a result of the hostplant switch, the numbers of Baltimores in this part of Bristol County increased explosively in the next few years, one field producing over 10,000 adults in July 1989 (Mello and Hansen 2004: 46).

In a separate discovery in 1989, Don Adams led Brian Cassie, George Leslie, and others to a large colony in an old pasture near Hockomok Swamp in West Bridgewater, where Baltimores had been present for several years with plantain as the sole host for eggs and young larvae. As with most plantain sites which are not mowed, this colony declined over time; by 1994 it had succeeded to buckthorn, Russian olive and other shrubs, and both plantain and Baltimores died out. But the site was the original source of butterflies for Don Adams’ now-thriving and well-managed colony in his West Bridgewater backyard (D. Adams, pers. comm. 6/19/2011). (Click here for a 2012 photograph of Baltimore Checkerspot eggs on plantain in West Bridgewater.)

Baltimore Checkerspots in Massachusetts have always been a wet meadow species, as Scudder’s account emphasizes. Chelone glabra or “snakehead” was a familiar wet meadow wildflower in the 19th century. Mrs. William Starr Dana wrote in her classic How to Know the Wildflowers that she had never met a turtle-head “which had not gotten as close to a stream or a marsh or a moist ditch as it well could without actually wetting its feet (Dana 1893; 1898 printing: 124).” Plantain, on the other hand, both lance-leaved and round-leaved, is an aggressive plant which arrived with European settlers and was known to Native Americans as “the white man’s foot.” It thrives in both wet and dry meadows, so that Baltimores may now often be found on drier sites, although these are often just upland from a wet area.

Mowing is usually necessary to maintain a Baltimore colony in New England. For colonies using turtlehead, if stands of the plant can maintain themselves without mowing, that is preferable; but often turtlehead is overwhelmed by aggressive goldenrod, asters and purple loosestrife in a moist meadow, and eventually shrubs may encroach. Mowing at a 6” height once a season in late fall (when larval nests are at ground level) is usually best for both turtlehead and Baltimores. Deer browse is another major threat to populations of turtlehead.

Colonies using plantain present more of a catch-22 situation. Fields must be mowed, often more than once, to prevent plantain from being shaded out, but that very mowing can destroy larvae at all stages, and also adults. There is no good point during the butterfly’s summer life cycle at which to mow. One mowing in late fall is probably best.

Where both primary host plants co-occur, Baltimore Checkerspots will switch easily from one to the other. Older, post-hibernation larvae will also feed on a great variety of adjacent plants, such as Viburnum dentatum, Rhinanthus crista-galli (rattlebox), Mimulus ringens, Gerardia (Agalinus) spp., Lonicera, Penstemon, and especially Fraxinus americana (ash) sapling leaves (Scott 1986; pers. obs., S. Stichter). However, females do not oviposit on these plants. The Connecticut Atlas found Baltimore larvae in the wild on Smooth False Foxglove (Aureolaria [=Gerardia] flava). Research is now underway to determine whether Baltimore caterpillars do better on one host rather than another. Both plantain and turtlehead contain iridoid glycoside chemicals which enhance larval growth and make them distasteful to birds; but Chelone contains more of these than Plantago. The adoption of plantain should not be entirely a surprise, since Euphydryas species in western United States also use Plantago lanceolata, as do several butterfly species in Great Britain and Europe (e.g. Heath and Glanville Fritillaries in England).

Baltimore Checkerspot ranks as “Common” according to MBC records for the years 2000 to 2007 (Table 5); the number of individuals reported is about on a par with Peck’s Skipper or Eastern Tailed-Blue. Two other wet meadow species, Harris’ Checkerspot and Bronze Copper, rank as “Uncommon,” while Silver-bordered Fritillary is Uncommon-to-Common.

The 1986-90 Audubon Society Atlas described Baltimore Checkerspot as “locally common.” In the Atlas species account, Brian Cassie suggests that it might be becoming more numerous in southeastern Massachusetts, since it was “occasionally to be found in colonies of 1000 or more, rarely 5000 or more” owing mainly to the adoption of lance-leaved plantain. However, the large colonies using plantain have often proved to be temporary population explosions; the very abundance of the plant seems to lead to a “boom and bust” pattern. At least two very large colonies in southeastern Massachusetts have died out as a result of natural plant succession. Other colonies on plantain have succumbed to human-caused disturbance, such as mowing and housing developments; plantain is often found in already-disturbed soils targeted for further disruption.

Overall the Baltimore Checkerspot is probably more common today than in Scudder’s time. The decline of intensive agriculture and the preservation of wet meadows have contributed to this result. The Baltimore’s adoption of a new host plant and a more upland habitat by the 1980’s also increased the numbers, and the instability, of colonies.

Baltimore Checkerspot numbers may have increased over the 1992-2010 period; the Breed et al. (2012) study using MBC data with list-length analysis as a measure of effort showed a slightly increasing detectibility for this species, which is in marked contrast to the strong decline found for Harris Checkerspot.

The number of MBC sightings per total trip reports (Chart 48) does not show any trend toward increase or decline over the 18 years 1992-2009. This pattern for Baltimore Checkerspot is in contrast to the sharp decline seen for Harris' Checkerspot and the slow erosion of numbers seen for Silver-bordered Fritillary.

Chart 48: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Some of the variation seen in Chart 48 is due to the expansion and then die-off of plantain-based colonies. At least two large plantain-based colonies on private sites in Easton and in Canton have been eliminated by human mismanagement in recent years (M. Champagne, pers. comm. 6/22/2011). At Turkey Hill, a Trustees of Reservations property in Hingham, high counts of 1,000 Baltimores in 1999 and 2000 ( 6/19/1999 B. Cassie; and 7/2/2000 D. Larson) gave way to high counts of only 236 the next year ( 6/30/2001, M. Champagne), and 30 the next (6/29/2002, E. Nielsen). After that, the colony simply disappeared, perhaps because of mowing at the wrong time.

A final example comes from Mill Pond Recreation Area in West Newbury, where numbers have fluctuated greatly. The highest counts for this colony each year 2000 to 2013 are shown below:

|

Number Seen |

Year |

Date |

Observer |

|

205 |

2000 |

6/25 |

F. Goodwin |

|

no reports |

2001 |

|

|

|

60 |

2002 |

6/29 |

E. Nielsen |

|

24 |

2003 |

7/6 |

T. Whelan |

|

50 |

2004 |

7/3 |

S. Stichter |

|

54 |

2005 |

7/10 |

E. Nielsen |

|

200 |

2006 |

7/5 |

S. Stichter |

|

700 |

2007 |

7/8 |

E. Nielsen |

|

22 |

2008 |

7/6 |

E. Nielsen |

|

4 |

2009 |

7/19 |

D. Saffarewich |

|

12 |

2010 |

7/3 |

E. Nielsen |

|

23 |

2011 |

7/2 |

E. Nielsen |

|

no reports |

|

|

|

|

10 |

2013 |

6/23 |

S. Stichter |

Years of high population in 2000, and in 2006 and 2007, were followed by years of low numbers. The colony is in a field of no more than four acres, surrounded by forest, shrubs, or mowed lawn. In 2001 mud from pond dredging was dumped on half the area, which was then seeded with a meadow mix. The Baltimore area was reduced to about two acres, but then expanded as the new meadow mix took hold. This provided good habitat for a few years, through 2007, but by 2009, 2010, and 2011, the amount of lance-leaved plantain in the whole meadow had begun to shrink. It was being shaded out due to lack of mowing, and yet mowing the whole area would risk eliminating the small population. This population may be in danger of dying out.

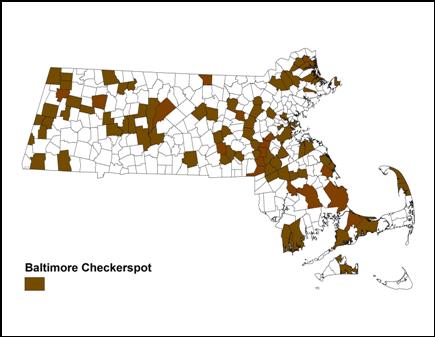

STATE DISTRIBUTION AND LOCATIONS

Baltimore Checkerspot is well distributed throughout the state, and was reported from 88 towns 1992-2013 (Map 48). The 1986-90 MAS Atlas found more blocs confirmed in eastern and southeastern Massachusetts than in the central and western portions of the state. BOM-MBC records also suggest a smaller number of Baltimore populations in the central part of the state, but add many reports, albeit of small numbers, from the valley and westward.

Map 48: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

Cape and Islands: In 1943 Frank Morton Jones wrote that "On Martha's Vineyard, in a few remote bogs, the Turtle-head, Chelone glabra, is present in small numbers, but this plant has never been detected on Nantucket; and not until 1941 was its butterfly associate, Euphydryas phaeton, found as a small larval colony on Martha's Vineyard." Jones found the larval nest on Tea Lane in Chilmark. (Jones and Kimball 1943: 15, 30). Today Baltimore Checkerspot is still found on Martha’s Vineyard. There are several discrete colonies, but overall they are uncommon and local. Most colonies are using lance-leaved plantain as the sole host plant today (Pelikan 2002; Pelikan pers. com. 6/13/2011).

For Nantucket, neither MBC records nor the 1986-90 MAS Atlas show any Baltimore Checkerspot reports, nor do Jones and Kimball cite any historical records. The Yale Peabody Museum and the Harvard MCZ do not apparently have any historical specimens from either island, and the Maria Mitchell Museum on Nantucket has no specimens (LoPresti 2011).

The species is found at many locations on Cape Cod, using both turtlehead and lance-leaved plantain as host plants. Colonies using plantain occur or have occurred in Truro (Twinefield), Barnstable (Marstons Mills Airport), Eastham (Fort Hill), Brewster (Higgins Windmill), and Falmouth (Crane WMA). A colony using turtlehead has been reported at Brewster Cape Cod Museum of Natural History (Mello and Hansen 2004).

Berkshires: Baltimore Checkerspots are found throughout the Berkshires, and are normally reported in good numbers on the Central, Southern and Northern Berkshire NABA Counts. However, there have been no “boom” numbers reported from any single location, as there have been in eastern Massachusetts. Alford, Cheshire, Lenox, North Adams, Sheffield, Stockbridge, Pittsfield, Richmond, and Williamstown have colonies which have been reported in MBC records. In the Atlas years, Ashley Falls, Becket, Richmond, and Sheffield were towns in which at least one was found. From the 1960’s, specimens in the Yale Peabody museum document the species’ presence in Richmond, Mt. Greylock, Hinsdale, and Becket.

Franklin Co.: Baltimores have been reported in good numbers every year since 1992 on the Central Franklin County NABA count. BOM-MBC has records from Ashfield, Colrain, Greenfield, Gill, New Salem and Shutesbury in this county (Map 48); the Atlas had reports from Deerfield, Hawley, Heath, Leyden, Northfield, and Orange.

Larger locations: Among the sites which have reported larger numbers of Baltimore Checkerspots 2001 through 2013 are

Ashfield Bullit Res. 65 on 7/6/2012, J. Richburg and T. Gagnon; Barnstable Marstons Mills Airport 500 on 6/27/2012 J. Dwelly; Dartmouth Allens Pond WS Field Station 20 on 6/28/2010 L. Miller-Donnelly ; Duxbury Bay Farm 13 on 7/12/2012 B. Bowker; Edgartown 140 on 7/14/2009 on private property, M. Pelikan; Falmouth Coonamesset Res. 100 larvae 6/8/2011 A. Robb; Grafton 231 on 7/6/2013 on private property, E. Barry and D. Price; Greenfield 16 on 7/6/2013, B. Benner and J. Wicinski; Harvard Stow Rd. CA 102 on 7/4/2004 T. Murray; Harvard Williams Land 98 on 7/6/2004 R. and S. Cloutier; Hingham World’s End TTOR 843 on 6/24/2012 B. Bowker et al.; Ipswich Appleton Farms 17 on 7/5/2013 H. Hoople et al.; Lenox 6 on 7/20/2013 B. Benner; Newburyport Maudslay SP 11 on 7/7/2012, B. Zaremba; North Adams 20 on 7/14/2007, F. Model and E. Nielsen; North Andover Stevens-Coolidge House TTOR 15 on 6/26/2010 H. Hoople, Weir Hill 20 on 7/7/2011 H. Hoople; Plymouth Tidmarsh Farm 13 on 6/30/2012 S. Stichter et al.; Raynham Borden Colony 9 on 6/24/2013 J. Dwelly; Sheffield Lime Kiln Rd. 9 on 7/8/2011, T. Gagnon; Shutesbury 1057 on 7/3/2006 T. Gagnon and C. Gentes; Stockbridge 10 on 7/13/2003 P. Weatherbee; Truro 114 on 7/7/2001, A. Robb, but none 2010-2013; West Bridgewater Adams Farm, 350 plus eggs on 6/23/2012, D. Adams; Weymouth Naval Air Station 54 on 7/9/2003 E. Nielsen; Williamsburg Graves Farm 13 on 7/17/2009 B. Benner; Williamstown Field Farm TTOR 10 on 6/29/2004 P. Weatherbee; Williamstown, Mountain Meadow Preserve, 13 on 7/11/2001, P. Weatherbee; Windsor Moran WMA 6 on 7/12/2007, F. Model; Wrentham 200 larvae and 40 adults on private property 6/27-29/2011, M. Champagne.

Like Harris’ Checkerspot, Baltimore Checkerspot has one concentrated flight period. MBC records 1992-2008 show nearly all sightings taking place between mid-June and mid-July: see http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp. Baltimores have only one brood each year.

Earliest sightings: In the 21 years of BOM-MBC records 1993-2013, the six earliest "first sightings" were 6/1/2002 East Bridgewater, E. Giles; 6/4/2012 West Bridgewater, D. Adams; 6/5/2010, West Bridgewater, D. Adams; 6/8/2013 West Bridgewater, D. Adams; 6/9/2001 Milford railroad power line, R. Hildreth; and 6/11/2011 West Bridgewater, D. Adams. All of these early dates are fairly recent - 2001 or later. The exceptionally warm springs of 2012 and 2010 are reflected in these records. As can be seen, the earliest reports often come from Don Adams" "Baltimore Farm" in West Bridgewater, south of Boston, where he keeps a close eye on his carefully tended colony.

In seven of the 21 years 1993-2013, the first report of a Baltimore Checkerspot adult came in the first or second week of June (June 1-15). In the majority (twelve) of these 21 years , the first report came in the last two weeks of June (June 16-30). (In the remaining two years, the earliest fliers were obviously missed.)

The beginning of the Baltimore flight may be advancing somewhat compared to the late 19th century. Scudder writes “ the earliest butterflies appear in the southernmost part of new England at the very end of May or in the first days of June; about Boston they are seldom seen before the 12th of June and they become abundant a very few days after their first appearance.... By the 15th or 20th of July they have usually disappeared even in the northern parts of New England (1889: 700).”

Latest sightings: In the 21 years under review, the latest "last sighting" dates are 7/26/1997 Central Berkshire NABA; 7/25/2004 Hadley, M. Faherty; and several 7/24 reports. The latest Baltimore reports often come from the mid-July NABA Counts, particularly the Northampton and Central Berkshire counts. Numbers are usually waning by the third week of July (see flight chart), but stragglers may persist longer now than in Scudder's day.

Occasionally lingering individuals have made it into August; examples are the sighting of singles on 8/8/1992 Stoughton, R. McGrath, and 8/1/2009, Newbury, S. Stichter. In one amazing case, a fresh individual was found in October: 10/15/2013 Dartmouth Allens Pond, M. Champagne (photo). This may have been an attempt at a partial second brood. Scudder did not mention this phenomenon, so perhaps it did not occur a century ago.

Baltimore Checkerspots need open sunlit wet meadows with turtlehead or plantain, in which mowing is delayed until late fall. Plantain may be "everywhere," but the butterfly cannot persist in the abundant plantain in urban backyards, shopping mall plantings, strawberry fields, or hayfields mowed three times a year. Increased development and build-out, and the expansion of local agriculture, all leading to a decline in open, lightly managed wet meadow, are probably the major threats to this species in Massachusetts.

But another threat is the natural succession of moist meadows back to shrub and forest. Unless management through light mowing or light grazing is undertaken, Baltimore Checkerspot habitat will decline. Turtlehead and plantain will be shaded out. The 1995-99 Connecticut Atlas found that although Baltimores were still ranked S4 or apparently secure in that state, the total of only 34 project specimens compared to 99 pre-project suggested some decline, due mainly to succession in meadow habitats (O'Donnell et al. 2007: 293).

Baltimore Checkerspot may be declining in all the mid-Atlantic states (Dworkin 2009) for a complex of reasons, including climate warming. In Maryland results of a Rare Butterfly Survey in 2003-03 confirmed the species' decline. Only 5 large populations remained, and a habitat restoration, captive rearing, and species reintroduction project was begun (Dworkin 2009). The reasons for the decline in Maryland were many, including land use changes, deer, and introduced parasitoids, but an additional factor was climate warming, which helped push the species out of lower elevations.

At the southern end of the Baltimore Checkerspot's range, such as in Maryland, the species may be vulnerable to climate warming, but this is probably not the most salient threat in Massachusetts. Habitat loss and mismanagement are by far the greatest risks.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-16-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS