ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

08 West Virginia White Pieris virginiensis W. H. Edwards, 1870

Host Plants and Habitat Relative Abundance Today State Distribution and Locations Broods and Flight Time Outlook

A delicately beautiful resident of rich deciduous forests, flying only in the spring, the West Virginia White specializes on the spring ephemeral toothworts Dentaria (=Cardamine) diphylla and D. laciniata (=concatenata).

A close relative of the Mustard White, the West Virginia White is more restricted to moist woodland habitats, and to the host toothworts, and has only a single brood each year, rather than several. It is less adaptable than the Mustard White (for example, less tolerant of garlic mustard), and is widely agreed to be in decline over a large part of its northeastern range (Schweitzer et al. 2011; NatureServe 2010; Cech and Tudor 2005; Gochfeld and Burger 1997: 131; Shapiro 1974).

It was not until the 1950s that West Virginia White was accepted as a distinct species (Klots 1951). Where populations of the two fly together, as in several Massachusetts locations, they do not normally interbreed, and the few known natural pairings have proved infertile (Chew 1980; Scott 1986: 219; Porter 1994).

Photo: Cummington, Massachusetts, 13 May, 2007 B. Spencer

Scudder subsumed Pieris virginiensis Edw. under Pieris oleracea--- he saw it as a darker-veined spring form of the Mustard White (1889: 1191). As a result, we lack knowledge of the West Virginia White’s early status in Massachusetts, but it was probably found throughout our mesic deciduous forests. West Virginia White undoubtedly suffered from the deforestation of the agricultural era in the 1700s and 1800s, and apparently did not adapt by utilizing new agricultural crops and new weedy crucifers, as the Mustard White did (Table 1: 1600-1850).

As Massachusetts reforested to some extent in the 20th century, populations of this species may have recovered somewhat, though we have no direct evidence of this, nor do we know how easily its host plants re-colonize in second-growth forests. By 1990’s,West Virginia White had not re-colonized second-growth forests in Ohio, and was reported reluctant to cross open areas (Iftner et al., 1992).

The earliest documentation of West Virginia White in Massachusetts comes from mid-1960’s specimens in the Yale Peabody Museum. A colony was found and a number of specimens taken on May 9, 1964, near West Mount, Pittsfield (D. S. Chambers); and two specimens from May 16, 1964 come from Dalton (C. G. Oliver). According to one 1976 Lepidopterists’ Society report “P. virginiensis was common in Dalton, (Berkshire) on the 30 April ( LSSS 1976). In 1983 it was reported from Chester Center (Hampden) in May by H. Pavulaan (LSSS 1983). Aside from these, there appear to be no other reports until the Massachusetts Audubon Atlas in the late 1980s.

West Virgina White’s two usual host plants are Cardamine [better known as Dentaria] diphylla, Two-leaved Toothwort, and Cardamine [=Dentaria] laciniata (=concatenata), Cut-leaved Toothwort. The 1990-95 Connecticut Atlas raised West Virginia Whites on both these early spring woodland wildflowers. The hosts are native to and found in all four western Massachusetts counties (Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire, Hampden) (Sorrie and Somers, 1999; Magee & Ahles, 1999), and perhaps this butterfly was always confined to these counties.

Another possible host (Scott 1986) is Cardamine pennsylvania, Common Bittercress, which is native to and found in all Massachusetts counties (Sorrie and Somers 1999). Another is Arabis laevigata, Smooth Rock Cress (reported in Ohio, Iftner et al. 1992), which is native to a few western Massachusetts counties. In the lab, West Virginia White will accept many other brassica hosts (Scott 1986), but in general West Virginia White --- unlike the Mustard White --- has not adopted a new non-native larval host plants, and is not among the butterfly "Switchers" (Table 3).

The habitat of the butterfly and its host plants is intact mesic deciduous forests. These kinds of forests were probably not present or widespread in eastern and southeastern Massachusetts even before the arrival of Europeans. The required host plants are forest floor constituents, which are widely threatened by deer browse (Schweitzer et al. 2011;NatureServe 2010).

In comparison to other Whites, the West Virginia is more restricted in host plant choice, and in addition does not colonize well. According to many observers, it is reluctant to fly across large breaks in forest canopy, although adults do move around within the forest and will cross canopy-covered dirt roads (NatureServe; Schweitzer et al. 2011: 151). Thus, woodland fragmentation poses a distinct threat. The West Virginia White's geographic range is more southerly than that of the Mustard White, and in New York and Pennsylvania its rich woods habitat is rapidly being fragmented and lost to development, deer overpopulation, and invasive plants.

An additional constraining factor is that the West Virginia White is only single-brooded, whereas the Mustard White is capable of two or three flights a season. The fact that it is single-brooded is probably an adaptation to the early senescence of Dentaria; a summer generation would have no host plant on which to complete its larval development. Cech (2005) terms the West Virginia White a “medium specialist,” whereas the Mustard White is a “medium generalist.” The latter is actually a more mobile and adaptable species.

A new threat in recent years is the spread of non-native garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), which invades even wooded sites, choking out larval foodplants. Female West Virginia Whites are attracted to this plant, and oviposit on it, but the larvae usually die before completing their development. Garlic mustard is thus serving as a toxic decoy and a population sink for P. virginiensis (Porter 1994; Courant et al. 1994; NatureServe 2010). Schweitzer et al.(2011) believe that the spread of garlic mustard into forests is the most serious of several threats to West Virginia White populations, noting that disappearance of the butterfly at several northeastern locations has coincided with the spread of this invasive plant. It is possible that P. virginiensis could adapt to this plant either through female avoidance of it or larval survival on it, but there is little evidence of that so far, and some feel that the very survival of the West Virginia White depends on whether it can adapt to this plant (NatureServe 2010). The more likely candidate for positive adaptation to garlic mustard is P. oleracea, the Mustard White. In new 2012 research, F. Chew and colleagues have shown that Mustard White larvae can have surprising survival rates on this plant (Chew et al., 2012).

The wasp Cotesia glomerata, introduced to control the Cabbage White, parasitizes that species, the Mustard White, and the Checkered White, but does not appear to so heavily affect the woodland West Virginia White, so far as is known (Wagner 2007). That parasitoid has now declined in Massachusetts, replaced by Cotesia rubecula, a more specialised parasitoid which attacks only the Cabbage White (Chew et al. 2012), and presumably not the West Virginia White.

The 1986-90 Massachusetts Atlas found West Virginia White “uncommon to locally common in wooded areas mainly at higher elevations from the Connecticut Valley westward.” It was confirmed in only 29 of 723 Atlas blocks (for towns, see Distribution, below), putting it on the lower end of Uncommon. MBC records likewise rank it as Uncommon (Table 5). The colonies appear to be small and scattered; the largest number reported from any one site in MBC records is 20. This is in contrast to the Mustard White, which has a few sites with larger numbers.

No change in relative abundance should be inferred from MBC sightings over this time period. In Chart 8, the apparently high number of individuals per report for 1993 is due to the very small number of reports that year (2, compared to at least 5 in all other years), one of which was an unusually high report of 20 from one town (Savoy 5/15/1993, E. Dunbar). The pattern of oscillation seen in Chart 8 could reflect actual population fluctuations, or variations in trip effort or on-site search effort.

Chart 8: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

MBC effort in the years 2006-2008 was more comparable than in earlier years, so that the decline shown for those three years might be real. It was the opinion of the Club record keeper, Erik Nielsen, that West Virginia White numbers were “on the low side” in 2007 compared to the unadjusted average for previous years back to 1994. Numbers seen were down again in 2009 and in 2010 compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994 (MBC Season Summaries 2008-2011), but the number of reports (effort) was also down in those years.

The Breed et al. (2012) list-length analysis of MBC data showed a non-significant 85% increase in detectibility of this species between 1992 and 2010.

State Distribution and Locations

While the West Virginia White population might actually be smaller than the Mustard White population, it is distributed over a much wider area within Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire and Hampden counties. Colonies appear to be many, but small: the largest count at any one site was 20 (Savoy 5/15/1993, E. Dunbar; for other locations see below).

The 1986-90 Audubon Atlas found West Virginia White in 23 towns, compared to only five for Mustard White. The towns were Becket, Blandford, Buckland, Clarksburg, Colrain, Deerfield, Egremont, Hatfield, Holyoke, Lanesboro, Monterey, Mt Washington, New Ashford, Pittsfield, Plainfield, Richmond, Rowe, Sandisfield, Sheffield, Tolland, Tyringham, Williamstown, and Worthington. These are all in Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire or Hampden counties.

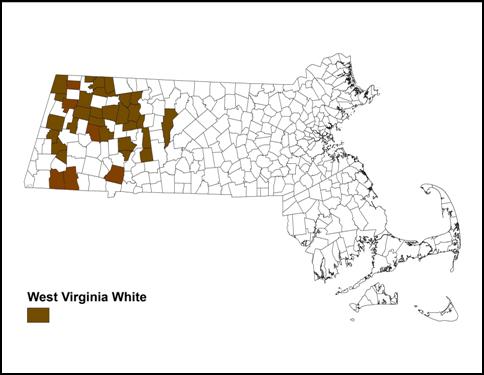

BOM-MBC records show West Virginia White seen in 34 towns between 1991 and 2013 (Map 8). This compares to only 10 towns for Mustard White. There is some overlap with the Atlas list of towns (New Ashford, Pittsfield, Rowe, Sandisfield, Williamstown, Worthington), but by and large this is a new and expanded list of towns where the West Virginia White is present.

Map 8: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

Map 8 generally confirms the earlier Atlas distribution: all sites are still in Connecticut River valley and westward, with most but not all at higher elevations. There are still no reports from Worcester County. The furthest west is a report from New Salem in Franklin County (3, 4/20/2006, B. Spencer)

Sites with the largest numbers are Mt Greylock (high count of 18 on 5/22/1999, T Gagnon; recent count 7 on 5/20/2010 T. Gagnon and B. Ripley), Williamstown area (10 on 5/11/2008, P. Weatherbee) and Williamstown Field Farm TTOR (4 or 5 on 5/2/2011, P. Weatherbee); Savoy (10 on 5/10/2002 P. Weatherbee); Chesterfield (max 12 on 4/20/2006 F. Model); Cummington (high count 7 on 5/9/2007 F. Model); Lenox (11 on 5/1/2004 R. Pease); and Worthington (8 on 5/9/2011 B. Spencer). West Virginia White was recently found in Westfield (8 on 5/5/2013, J. LaPointe (photos at

| http://www.flickr.com/photos/65348928@N04/sets/72157633412472465/ |

West Virginia White can also be seen at MAS Canoe Meadows in Pittsfield (uncommon, R. Laubach) and Windsor Notchview TTOR (4, 5/24/2007, B. Spencer and J. Richburg).

A small colony in Sunderland was found in 1998 by Diane Potter, and followed for several years by Dottie Case. This site became a favorite with Club members and was visited almost every year from 2000 onward. The high counts each year varied from 4 to 12. But overgrowth of Japanese knotweed was reported in 2009-2010, and the site was seriously threatened by logging in 2013. Recent high counts at this site were 5 on 4/6/2000 D. Case; 8 on 5/4/2003 T. Murray; 7 on 5/11/2004 D. Case; 4 on 5/9/2005 S. and R. Cloutier; 4 on 5/5/2007 B. Benner et al.; 5 on 5/2/2009 S. Moore and B. Volkle; 6 on 5/1/2010 S. Moore and B. Volkle; 12 on 5/1/2011 S. and R. Cloutier; 5 on 4/13/2012 S. and R. Cloutier (photos); but only 2 on 5/2/2013 S. and R. Cloutier, after logging of the site had taken place.

Some location details have been omitted from this account because of concerns about collecting. Butterfly collecting on Trustees of Reservations and Massachusetts Audubon properties is prohibited without a permit from the organisation. Collectors are asked to refrain from collecting this uncommon species at any location.

As noted, West Virginia White has only one brood, flying between early April and mid-June (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp) . The short spring flight period is likely an adaptation to the early senescence of its main host plant, Dentaria.

Earliest sightings: In 23 years of BOM-MBC data 1991-2013, the four earliest observation dates are 4/6/2000 (Sunderland, D. Case), 4/8/2010 (Whately, B. Benner), 4/12/2012 (Sunderland, R. and S. Cloutier), and 4/13/1999 (Lee, P. Weatherbee). Larger numbers emerge in the last two weeks of April, and the peak flight time is the first three weeks of May.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years of observations (1991-2013), the five latest dates are 6/13/2006 (T. Gagnon), 6/12/2005 (M. Lynch and S. Carroll), 6/8/1997 (R. Cech); 6/6/1999 (M. Fairbrother); and 6/5/2013 (T. Gagnon). ALL of these late reports are from Mt. Greylock. These early and late dates are similar to those found during the Atlas period. Due to its early flight period, this species is not found on the NABA Fourth of July counts.

After a review of this species in 2010, NatureServe (http://www.NatureServe.org/explorer/ ) concluded “The West Virginia white has declined greatly or disappeared in its core range from the New York City suburbs to the northern North Carolina mountains.” The species is now apparently declining in Connecticut, Pennsylvania and New York, and was extirpated decades ago in New Jersey. Threats are expected to increase, and the outlook for this species in much of its range is “bleak.” A recent survey of rare lepidoptera in eastern forests came to a similar conclusion (Schweitzer, Minno and Wagner 2011).

The 1995 Connecticut Atlas found only 11 project records, compared to 33 pre-project, but for some reason did not conclude that the species was declining. That Atlas did note that “some historic colonies evidently no longer exist.”

West Virginia White has a limited range in North America. It is confined largely to the Appalachian Mountains, parts of Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin and Michigan, and a few localised areas in Canada (Opler and Krizek 1984; Layberry 1998; NatureServe 2010). It formerly extended continuously south in the Appalachians to northern Georgia, but NatureServe reports an “alarming decline” extending to northern North Carolina, and if this is true the range is in danger of fragmentation. Massachusetts is at eastern edge of the species’ range, and is one of the few states with numerous colonies where decline has not yet been reported.

As noted, the spread of garlic mustard may be accelerating the decline of this species, and its survival may depend on whether it can adapt to garlic mustard. Even if genetic adaptation does occur, this is unlikely to be fast enough to save many small populations, and the species’ abilitiy to recolonize over open areas is weak.

In addition, as a higher-elevation species, the West Virginia White will probably be negatively affected by climate warming (Table 6); this factor could account for its decline in states further south, but apparent stability so far in Massachusetts and Vermont. Variable precipitation due to climate change is also a factor; in very hot, dry springs, some or all of the larvae may starve due to early senescence of the host plants (NatureServe 2011). Deer browse, forest fragmentation, and introduced parasitoids are additional serious threats.

The West Virginia White should be placed on a Watch List in Massachusetts, and reviewed for possible listing as a protected species under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. Given its history in other eastern states, its status here should be more carefully monitored.. It is ironic that the more adaptable Mustard White is state-listed as Threatened, whereas the less-adaptable West Virginia White is not listed.

Field work should be initiated to pinpoint the location of all reported colonies. A select group of colonies should be monitored frequently, and programs of garlic mustard removal should be initiated. Research on host plant use should be undertaken. Where it is not already, collecting specimens without a permit for scientific research should be prohibited, since small colonies may not survive the loss of females.

NatureServe (2010) concludes ”this species is unusually vulnerable to forest fragmentation and is now seriously threatened in some parts of its range by rampant growth of garlic mustard into its habitat and probably by out of control deer. These last two threats are expected to increase. While the species is still fairly widespread in some states like New York, it is declining or has already declined or become extirpated in several others in recent decades and is not secure in substantial parts of its range and almost certainly faces a substantial decline and probably a range reduction in the next few decades...”

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 5-23-2014

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS