ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

07 Mustard White Pieris oleracea [= napi] Harris, 1829

History Host Plants and Habitat Relative Abundance Today State Distribution and Locations Broods and Flight Time Outlook

The Mustard White, the West Virginia White (Pieris virginiensis) and the Checkered White (Pontia protodice) are our three native whites in the northeast. Their decline over the last 150 years is often attributed to the introduction of the Cabbage White (Pieris rapae) from Europe. But direct competition from the imported species has not been demonstrated, and the decline of the native whites may be more plausibly related to the spread of non-native crucifer host plants, to which native butterflies were not adapted, to the decline of woodlands, and to introduced parasitoids carried by the Cabbage White.

The Mustard, West Virginia and Cabbage Whites are closely related genetically and are part of a holarctic P. napi “species complex.” The Mustard White is sometimes referred to as Pieris napi oleracea. It apparently does not interbreed with the Cabbage White in Europe or in Vermont (Chew 1981), and the few known natural pairings with West Virginia White have proved infertile (Chew 1980).

Photo: Mustard White on Cuckoo Flower, Lenox, Massachusetts May 13, 2011 F. Model

The introduction of the Cabbage White from Europe, and the concomitant decline of our native whites, is a fascinating story, documented in extensive detail for New England by Scudder. The new butterfly was first found in Quebec about 1860, and spread rapidly south, east and west, arriving in Massachusetts about 1870 (Scudder, 1889: 1181 and map). It spanned the continent by 1900. Before the Cabbage White, the two whites regularly in New England were the Mustard White and the West Virginia White.

Scudder and Harris did not separate these two, treating the West Virginia White as simply a woodland race of the Mustard White. Thus their accounts of the decline of P. oleracea ---presumably from “competition” with the Cabbage White---actually refer to both P. oleracea and P. virginiensis. But since Scudder described a distinctly northerly and higher-elevation range for P. oleracea, and since the West Virginia White has a more southerly range, and also is now known to be almost always confined to forest under-stories and its traditional larval host plant, Scudder and Harris’ accounts are usually taken to refer mainly to Mustard White.

Harris was the first to describe oleracea in 1829. He had no Mustard White specimen in his 1820-26 Boston area collection, but did have 5 specimens, both male and female, taken May 11, 1826, at Round Hill in Northampton (Index Lepidopterum). In his 1841 report he says oleracea is found only in northern and western Massachusetts, where gardens and fields may be ‘infested’ with them. He writes “About the last of May, and the beginning of June, it is seen fluttering over the cabbage, radish, and turnip beds, and patches of mustard, for the purpose of depositing its eggs.” And again, “I have seen these butterflies in great abundance during the latter part of July, and the beginning of August, in pairs, or laying their eggs for a second brood of caterpillars” (Harris, 1841: 214-5). He recommends that gardeners destroy all caterpillars. In this period, then, it was the Mustard White and not the Cabbage White which caused the Brassica crop damage in New England farms and gardens.

Scudder appears to think that P. oleracea was once not uncommon in eastern Massachusetts, and in particular recalls ("I think it was about 1857") finding Mustard Whites "swarming" in Harvard Yard, Cambridge. Since then, he writes, “the invader [the Cabbage White] has nearly exterminated the indigenous species." The Mustard White “ is now never found to my knowledge anywhere in the region about Boston,” and had retreated to western Massachusetts. He also recorded (sometime around 1865) that “Mr. Bacon of Natick, Massachusetts, says that the insect by no means disturbs cabbages and turnips as it did fifteen or eighteen years ago” (Scudder 1889: 1198). F. H. Sprague collected actively in the Boston area between 1878 and 1895, and he did not find any P. oleracea. There are only three Mustard White specimens from Massachusetts in the Harvard MCZ general collection, and none of them have any date or location. F. H. Sprague did have a record from the highly unusual location of Marblehead, September 1914, but the species had "not been seen since” in that area (Farquhar 1934).

Farquhar 1934 lists Massachusetts records only from Williamstown (2 specimens, C. A. Shurtleff and S. H. Scudder); Monterey Aug 4, 1920 (C. A. Frost); Marblehead 1914 (F. H. Sprague); Weston; Williamsburg; and Hinsdale (F. Knab). Some of these could be records of West Virginia White, since that species was not yet distinguished. With the exception of the Weston and Marblehead reports, and Scudder’s earlier Cambridge and Natick reports, the remainder of the early reports are from western Massachusetts. It seems probable that the Mustard White occurred only rarely in eastern Massachusetts.

Between 1600 and 1850, Mustard White probably increased in Massachusetts compared to the pre-settlement era (Table 1). During this period, the expansion of farming created new open meadows and gardens with new larval hosts which supported Mustard White's second and third summer broods, while many forests and wetlands still remained to support the spring brood.

But Mustard White has declined significantly in Massachusetts since about 1850 (Table 2) (NHESP 2/2010). In explaining this decline, Chew (1981: 667-9) has rightly focused on the presence or absence of a suitable host plant for the spring brood. While Scudder and Harris report P. oleracea fluttering in great numbers around garden plots, garden crops could only function as larval hosts for the summer broods. Chew writes that only the native perennial Dentaria diphylla, the introduced biennial Barbarea vulgaris, and possibly the native Cardamine and Rorippa spp. in wet meadows and river edges could have functioned as spring larval hosts. B. vulgaris, while widely established in New England by at least the mid-1800’s, only marginally supports Mustard White larval growth. So the loss of rich forest under-stories with D. diphylla, and wet meadows with Cardamine, may have been the main factor which ultimately reduced Mustard White populations in both eastern (if it occurred there) and western parts of the state. Native species of Cardamine, Rorippe and Dentaria were probably always more prevalent in the western and central parts of the state.

Scudder tells us that while P. oleracea was “constantly seen flying about garden plots in the vicinity of turnip beds,” its native haunts were actually the borders of woods where wild Cruciferae grow. (My emphasis). “In the White Mountains one quickly notices the difference in this respect between it and P. rapae, the latter confining itself almost exclusively to the neighborhood of houses or the high road, in contradistinction to the habits of the present species, which prefers open places in the woods and forsaken roads through them, seldom occurring in the vicinity of cultivated ground” (Scudder 1889: 1203). Chew (1981) points out that it is in spring, when the native toothwort is being used as a larval host, when the Mustard White most critically utilizes woodland openings.

Today Mustard White can be found in openings in mesic forest, but also in riparian floodplains, margins of fens, marshes and streams, and wet meadows, fields and pastures (NHESP 2/2010).

The largest known Mustard White colonies in Massachusetts today are found in open, damp meadows. These populations feed mainly on Cardamine pratensis var. pratensis, a variety of Cuckoo-flower introduced from Eurasia, which grows in meadows, lawns and roadsides. This plant, like the native toothworts but unlike many other imported crucifers, is available to host the spring brood of Mustard Whites, as well as later broods. On this plant, larval growth rate is fast and survivorship high (NHESP 2/2010 M. Nelson; F. Chew unpub. data). In adopting this non-native larval host, the Mustard White has once again proved to be quite adaptable.

Mustard White’s original native host plants include Toothwort (Dentaria=Cardamine diphylla and concatenata), Tower Mustard (Arabis glabra), Wild Peppergrass (Lepidium virginicum), Wild Radish (Rhaphanus raphanistrum), Marsh Yellow Cress (Rorippa palustris), and Fen Cuckoo-flower (Cardamine pratensis var. palustris) (Leahy, MAS Atlas; NHESP Fact Sheet; Sorrie and Somers 1999). Scudder adds Arabis drummondii and perfoliata (1889:1199).

Mustard White is thus among the many butterfly “Switchers” (Table 3). Judging from historical reports, the Mustard White adapted quickly and successfully to imported garden crops of turnips and cabbages, which were cultivated varieties of old-world Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea, and to cultivated radishes (Raphanus sativa), horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) and mustard (Sinapis) (Scudder 1889:1199; Chew 1981; Sorrie and Somers 1999). It actually became a garden pest. Mustard White also used some of the new exotic weedy species rapidly spreading in the 19th century; it apparently used such new weeds such as Early Winter Cress (Barbarea verna), Rape (Brassica rapa), Black Mustard (Brassica nigra), and Watercress (Nasturtium officinale), and to some extent Common Winter Cress (Barbarea vulgaris). We do not know precisely when most of these new weeds arrived here. Chew (1981) has made the point that most of these crops and weeds were available only for the second or third summer broods; thus, the presence of nearby forests with toothwort remained a necessary part of Mustard White habitat during this time. She has also shown that the species is attracted to and will lay eggs on two now-abundant alien weeds, Common Winter Cress (Barbarea vulgaris) and Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), but the larvae do not survive. These weeds function as population decoys or sinks.

A now rapidly spreading new alien, Garlic Mustard (Alliaria officinalis), may also be functioning as a population sink, but there is some evidence that the Mustard White butterfly may be successfully adapting to it. In 1990 in Lee, Massachusetts, Roger Pease observed P. napi ovipositing on garlic mustard in July, and he successfully reared the eggs on it, producing adults with summer brood phenotypes. In 1993 A. V. Courant and others at Tufts University successfully replicated this rearing: 34 P. napi larvae from a Lee area female hatched and were reared on garlic mustard in the lab. Fourteen—but only 14--- successfully pupated and produced adults. Pupal weights were similar to those of others reared on another mustard plant, but larval development took significantly longer on Alliaria (Courant et al. 1994). Other similar rearing evidence is accumulating, and several authors (Chew, Van Dreische and Casagrande 2012; Keeler and Chew 2008) speculate that since Alliaria is a widely used and suitable host for related P. napi species in Europe, the North American P. napi oleracea may be in the process of adapting to it.

In Massachusetts the wasp parasitoid Cotesia glomeratus was introduced in the 1980s to control the Cabbage White, and it became widespread. It was found to have infected Mustard White populations as well, and may have played a role in their decline (NHESP 2/2010; Wagner 2005: 84). By 1988 a second wasp, Cotesia rubecula from China, was released in Deerfield, Massachusetts, then later at 17 other locations around New England. By 2002 it had been recovered from many locations, and it may have displaced C. glomeratus regionally. This would be good news, since rubecula apparently does not attack the Mustard White (J. Boettner, pers. com. 2/ 2011).

The 1986-90 MAS Atlas found the Mustard White rare and local in Massachusetts, occurring only at higher elevations west of the Connecticut River Valley. It was confirmed for only 5 out of 723 quadrangles, with reports from the towns of Lenox, Pittsfield, Washington, Westhampton (Hampshire Co.), and Windsor ---all but one in Berkshire County. Observers since then have documented larger populations, at more sites, and according to MBC records 2000-2007 Mustard White would now rank as “Uncommon to Common,” rather than Rare (Table 5). However, this is largely an artifact of one very large report (280 in 2004 at one site), and several large totals from Fourth of July Counts, and the rank should probably be Uncommon. The West Virginia White is also ranked as “Uncommon.”

Chart 7. MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

No population trend should be deduced from Chart 7. Any upward trend is likely the result of increased observer effort; interest in this species has been high. The spike in 2004 reflects the unusually high total of 280 reported in 2004 by E. Nielsen, which may have been an unusual outbreak, or involved exceptional effort, since numbers reported from that site were lower in succeeding years. There are no other single-day reports larger than 102 in the database; not even the NABA Count reports. The highest Central Berkshire NABA count was 102 on 7/20/2003.

The Breed et al. 2012 list-length analysis of MBC data showed a slight upward trend for Mustard White, not statistically significant.

State Distribution and Locations

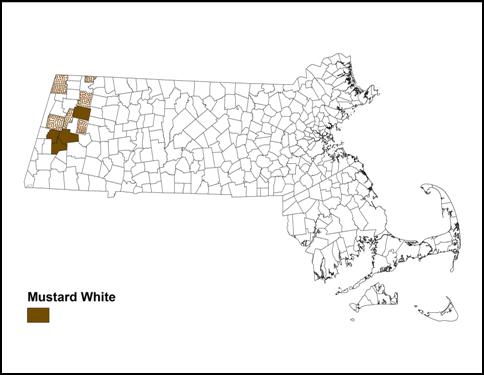

Map 7: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

Mustard Whites in Massachusetts are concentrated in six towns in the central Berkshires: Lenox, Washington, Lee, Windsor, Pittsfield, and Dalton. Virtually all MBC reports are from these six towns, and these are also the towns with colonies documented in the state Natural Heritage database (NHESP 2/2010 M. Nelson). On Map 7, the four primary towns with the most reports and highest numbers reported (Lenox, Washington, Lee, Windsor), are shown in brown; secondary towns, with only a few reports of 1-2 butterflies, are stippled. Secondary towns shown in BOM-MBC records are: Williamstown to the north (4/20/2006, P. Weatherbee), Savoy (5/25/2011, T. Gagnon), Peru (7/15/2011, S. Cloutier, photo on Facebook) and Monroe (Franklin Co.) in 1996. The map shows a total of 10 towns.

Mustard White was reported on the Northern Berkshire NABA Count in 1993 and 1997. In 1993, the first year of this Count, M. Fairbrother and E. Dunbar netted an individual to confirm the identification. The town location was not reported. Historically, Scudder had found it in Williamstown.

The most important and productive location has been the George L. Darey Wildlife Management Area in the floodplain of the Housatonic River in Lenox. Recent reports include a maximum of 280 on 8/8/04 E. Nielsen; 100 on 7/21/2010 T. Gagnon; 100+ on 6/14/2012 F. Model; 75-80 on 5/9/07 B. Spencer; and 50 on 6/18/2010 F. Model. Some of these estimates include other areas along New Lenox Road. Mustard Whites can also be found along Roaring Brook Road in Lenox (max 16 on 4/24/08, R. Pease). The butterfly can also be found at October Mountain State Forest (the majority of which is in the town of Washington) (max 10 on 5/26/1997 R. Pease); at MAS Pleasant Valley Wildlife Sanctuary in Lenox (where it is uncommon), and at Canoe Meadows Wildlife Sanctuary in Pittsfield (uncommon; max 8 on 7/19/1986 R. Miller). In Windsor, it can be found at Notchview Reservation TTOR (2, 5/24/2007 J. Richburg and B. Spencer); F. Model 2011 photo on flickr)

In the 1960’s (1964-68) C. G. Oliver collected many, many specimens of Mustard White in Dalton; these are now in the Yale Peabody Museum.

COLLECTORS PLEASE NOTE: THIS IS A STATE-LISTED SPECIES AND COLLECTING IS NOT ALLOWED WITHOUT A STATE-ISSUED PERMIT. The research must be by qualified persons and be compatible with the preservation of the species.

This is a Threatened Species under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA). If you find a Mustard White, the observation along with a photograph should be reported to the state Natural Heritage Program at http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/species_info/pdf/electronic_animal_form.pdf .

There are three broods; in some years the third brood is partial, while in others it is larger and may even include a fourth brood (NHESP Fact Sheet 2010).

MBC 1993-2008 records show three main flight periods: mid-April to mid-June; mid-July; and the second week of August to mid-September (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp ). MBC first brood dates begin a bit earlier than the “late April through May” time span reported elsewhere (NHESP Fact Sheet 2010).

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records 1991-2013, the six earliest sighting dates are from early April. Five are from the New Lenox Road site, observed by Roger Pease: 4/8/2000; 4/14/2002; 4/17/2004; 4/17/2005; and 4/17/2006, and one is from Windsor 4/16/2012, observed by T. Gagnon. Early visits have not been made systematically to either the Lenox or the Windsor sites.

Through 2008 it had been thought that the second flight did not begin until July, as shown in the Nielsen flight chart linked above, but in 2010 and 2012 F. Model photographed the lighter-veined summer form flying in Lenox as early as 6/18/2010, and 6/14/2012, two years with especially warm springs. Photos from both years are available at

On 6/18/2010 about 50 were seen, and on 6/14/2012 at least 100 were seen, with many mated pairs. A 6/10/2012 report from Windsor may also be the second flight.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years 1991-2013 the latest recorded flight dates are all from the Lenox site: 9/12/2006 (43), B. Spencer, and 9/6/2003 (7), R. Pease. These are the only two September reports; the next latest is 8/29/1999, R. Pease. The time period for the partial third flight, not distinguishable in BOM-MBC records, is listed as “late August and early September” on the NHESP Fact Sheet.

Scudder reports that “the first brood has been seen as early as April 18, but usually appears between April 27 and May 9” (1899:1201). He does not give a geographical reference for these dates, and they may refer to northern locales. If they referred to Massachusetts, the current sighting evidence would indicate a slight advancement of the timing of the spring flight since Scudder. As to late flight dates, Scudder refers to occasional late specimens found in late September/early October, perhaps a partial third brood, as is seen today. MBC observers have not systematically monitored the Lenox site in August or September, and MBC has records of a September flight in only two years. In at least one year, 2006, the late brood at the Lenox site was good sized (43 on 9/12/2006).

The Mustard White is at the southern end of its range in Massachusetts. As a northerly species, it could withdraw further north as climate warms (Table 6). Its NatureServe status is S1S2 in Massachusetts, or “critically imperiled”; continent-wide, it has already experienced some range contraction northward (http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/ ). However, it is an adaptable species, which is now doing well on an introduced host plant Cardamine pratensis.

Mustard White is state-listed as a Threatened Species, and the resultant land conservation and ongoing monitoring have been of great importance to this species. The state Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program lists the following continuing threats to the Mustard White: hydrologic alteration (in the cases where the riverine wet meadows are maintained by periodic flooding); introduced parasitoids (including the one intended for the Cabbage White); insecticide spraying; deer browse of larval host plants; and off-road vehicles. (NHESP 2/2010).

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013

page updated 11-18-2013

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS