ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

46 Harris’ Checkerspot Chlosyne harrisii (Scudder, 1864)

History Host Plants and Habitat Relative Abundance Today State Distribution and Locations Broods/Flight Time Outlook

Samuel Scudder named this small bright butterfly in honor of Thaddeus W. Harris, who died in 1856. The species was known to Harris from one puzzling specimen from Sutton, in central Massachusetts, sent to him by a Dr. Smith (Index; MCZ Harris Collection, n.d.). Harris wrote “I think it possible that this species may be distinct from ...” the species that Boisduval called ismeria (Harris 1862: 288). It remained for Scudder to conclusively describe it as a new species, which he did from a Pittsburg, N. H. specimen collected by J. O. Treat (Harvard MCZ Types Collection #26344). In Scudder's day Harris' Checkerspot was commoner north of Massachusetts, and "not known" south of this state (1889: 680; for background see Calhoun 2003).

Today, Massachusetts has again become the southern limit of Harris' Checkerspot's range, since the species appears to be withdrawing northward due to climate change. Harris' Checkerspot has not been found in Connecticut since the 1995-99 Connecticut Butterfly Atlas, despite searches; it is now listed as "possibly extirpated" in that state. And recent searches in southeastern Massachusetts have failed to find Harris' Checkerspot, although it was there in 1988.

Photo: Newbury, Mass. Martin Burns WMA, T. Whelan, June 19, 2006

Harris' Checkerspot is closely related to the Silvery Checkerspot (Chlosyne nycteis), which is at the present time extirpated from Massachusetts, having not been seen here since the few reports (Blandford, Lenox, Williamstown) in the mid-19th century (Scudder 1889: 663; no Mass. specimens in MCZ or Yale).

Early museum specimens from Massachusetts are not plentiful. In 1889 Scudder knew of records from only five Massachusetts locations -- West Roxbury, Malden, Sutton, Princeton (collected by Scudder himself), and Springfield ("rare")--, a fact which suggests that Harris’ was not common (1899: 680). In the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) the only early eastern Massachusetts specimens are six from Malden dated June 23, 1883, and one from Wollaston June 19, 1878, all by veteran collector F. H. Sprague. For central Massachusetts, the species' stronghold today, there is a June 14, 1908 specimen from Framingham (C.A. Frost, BU), and W. T. M. Forbes mentions finding Harris' in the Worcester area as early as 1909 (Forbes 1909). From the 1920’s there are MCZ and BU specimens from Weston (1920 and 1921, mostly bred, but larvae apparently collected nearby, C. J. Paine) and Tyngsboro (1929) in the east, and Winchendon (early '20s) and Groton (1932) mid-state.

Farquhar (1934) adds a few more known eastern Massachusetts locations --Salem, Saugus, and Stoneham -- and reiterates that Harris’ is “rare south of Massachusetts.” C. V. Blackburn's Stoneham specimen (n.d.) is at Furman University. At the Yale Peabody Museum, there are several 1960’s specimens from West Acton by C. G. Oliver, and some from 1981 from larvae collected in the vicinity of Sturbridge by L. F. Gall. There is a 1974 report of Harris' as "abundant" during its flight period in the Holliston-Sherborn-Framingham area (D. Willis, LSSS 1974). W. D. Winter collected Harris' Checkerspot in Dover in 1966 and 1974, and in Sherborn in 1974 (MCZ specimens).

Overall, prior to the 1986-90 MAS Atlas, Harris' was found mainly in central and northeastern Massachusetts, south to the Dover-Sherborn-Holliston area. There are no reports from the Connecticut River valley or further west. The Atlas confirmed that this species was rare in those regions.

Compared to pre-settlement times, the agricultural clearing initiated during the colonial era in New England probably increased wet meadow habitat for Harris’ Checkerspot (Table 1). However, the later loss of wet meadows to more intensive agriculture and to non-agricultural development, combined with the very local nature of this species, no doubt resulted in some decline in its numbers since 1900 (Table 2).

In Connecticut, the 1995-99 Connecticut Butterfly Atlas found only two Harris’ Checkerspots during intensive surveys, compared to 49 pre-Atlas records from 16 towns (O'Donnell et. al. 2007). And, the species has not been found since, despite searches. As a result, it is now ranked by NatureServe as SH, or "possibly extirpated" in Connecticut (NatureServe 2014). David Wagner suggests that introduced biological control agents, such as parasitic wasps and flies, and also loss of wet meadow habitat and aerial pesticide applications, may be responsible for the disappearance of both the Harris' Checkerspot and its congener the Silvery Checkerspot (Chlosyne nycteis) from that state (2007: 203). A warming climate should also be taken into account. The RINHS checklist for Rhode Island (Pavulaan and Gregg 2007) lists Harris’ as “status unknown,” but it is probably not present there.

Harris’ Checkerspot should be on a “watch list” for Massachusetts (see Outlook). We include it here as a Species of Conservation Concern.

NOTE TO COLLECTORS: This is a sensitive and probably declining species in Massachusetts and collectors are requested not to take specimens except as part of scientific research under institutional auspices. Massachusetts Audubon Society does not permit collecting on its properties, and The Trustees of Reservations requires a permitting process.

Harris’ Checkerspot is a quintessential northern “wet meadow” butterfly. We have four such wet meadow denizens in our state, the others being Baltimore Checkerspot, Silver-bordered Fritillary, and Bronze Copper. All of these are uncommon and face loss of habitat from agriculture, development, and natural succession. They may be at further risk because of food plant specialization and/or lack of adaptability to warmer temperatures. Harris’ and the Bronze Copper are the least common.

Harris’ sole larval food plant is flat-topped white aster, Doellingeria (formerly Aster) umbellatus, a tall native late-blooming composite which grows in seasonally wet areas between strict uplands and constantly wet areas. The butterfly has not adopted any new larval host plants so far as is known. At the continental level, the range of D. umbellatus is much wider and extends further south than that of the associated butterfly. In this state, while D. umbellatus may be found in every county (Magee and Ahles: Map 2346), the range of the butterfly is similarly not as wide as that of the food plant. Although NaturServe scientists assert optimistically that the species “is likely to colonize most good stands of its common foodplant,” in fact, Harris’ seems to require quite dense stands of Doellingeria, with females choosing only the largest plants on which to oviposit. Young larvae often denude this plant after hatching. Harris’s has only one generation a year, and the mortality of young larvae is high, many succumbing to predators and starvation as they move away from the birth plant in search of new aster stems. Further high levels of mortality occur during winter diapause (Dethier 1959; Williams 2002). Ernest Williams estimates that it may take 500 caterpillars to produce one flying adult the next season.

A photo of Harris' Checkerspot eggs on flat-topped white aster, taken June 23, 2007 at Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS by G. Kessler, may be found at http://garrykessler.zenfolio.com/p77944831/h37601664#h37601664.

Dispersal ability is critical to species such as Harris’ Checkerspot, which depend upon habitats that are subject to succession. While Doellingeria itself is a good colonizer of newly opened moist areas, Harris’ Checkerspot appears to be only a moderately active disperser (Williams 2002), although more research needs to be done. Individual colonies tend to be small; to persist, they need to be part of a larger meta-population, so that if some patches of habitat succumb to succession, other habitats will be available nearby. Small populations at a large distance from other colonies may easily die out.

The challenge that land managers face in preserving colonies of wet meadow butterflies like Harris’ Checkerspot is that mowing must at some point be done, sometimes even annually, but it must be coordinated with the butterfly’s life cycle. Mowing should not be done until late fall, after the larvae have finished feeding and settled down into the leaf litter to overwinter. Mowing height should not be less than 6 inches.

Relative Abundance and Trend Today

The Massachusetts Atlas found Harris’ in only 24 out of the 723 blocks covered; J. Choiniere aptly termed it “uncommon and local” in his Atlas account. MBC records also rank Harris’ as “Uncommon” (Table 5). Compared to our other wet meadow species, it is seen less frequently than the Baltimore Checkerspot or the Silver-bordered Fritillary, but more frequently than the Bronze Copper.

List-length analysis of MBC data by G. Breed et al. (2012), published in Nature: Climate Change, found a statistically significant 66% decline in detectibility of Harris' Checkerspot over the 1992-2010 period. This puts Harris' Checkerspot among the fastest-declining species in the state. Supportive evidence comes from the counts of numbers seen per total trip reports, and numbers per Harris' trip reports, in MBC data; these are seen in Charts 46a and 46b, which similarly indicate Harris’ Checkerspot's decline over these years.

Chart 46a: Sightings of Harris' Checkerpot per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

Chart 46b: Sightings of Harris' Checkerspot per Report Containing that Species, 1992-2009

In Charts 46a and 46b, 1992 may be an atypical year since a very small number of trip reports (less than half the number in 1993) produced surprisingly high numbers of butterflies. Even so, the 1993-2008 trend, in which the number of trips is more comparable, still shows a significant downward slide for this species.

The results for 1992 and 1993 reflect the very good numbers reported from the Holden WTAG radio tower site and the Worcester Broad Meadow Brook colony; both, but especially Holden (see below), appear to have declined over time.

Statistics published in the Massachusetts Butterflies season summaries show the same pattern of steady decline: the average number of Harris’ Checkerspot seen on a trip was down 38% in 2007, 81% in 2008, 61% in 2009, and 86% in 2010, compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994 (Nielsen 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011).

State Distribution and Locations

Harris’ Checkerspot has been reported from 38 towns in the twenty-three years 1991-2013, compared to 105 for Silver-bordered Fritillary and 88 for Baltimore Checkerspot.

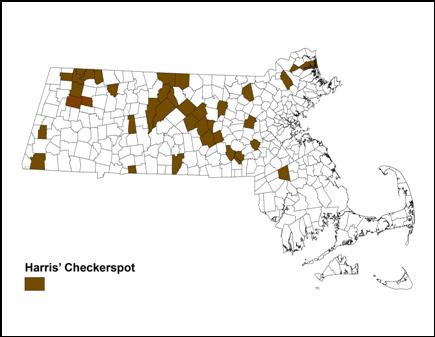

In the 1986-90 MAS Atlas, the majority of records were from central Massachusetts, with a scattering from northeast of Boston (Essex County). There were only two western Massachusetts records, in the towns of Washington (central Berkshire County) and Monroe (western Franklin County), and none in the Connecticut River valley. MBC sightings records (Map 46) add more colony locations, but generally confirm the concentration of this species in central Massachusetts.

There are no MBC reports from southern Bristol County, and the single 1988 Atlas report from New Bedford could not be relocated in 2011, though the reported location was searched (see below). Searches should continue, but if Harris' Checkerspot cannot now be found in southeastern Massachusetts, then it has undergone a range contraction within the state.

Map 46: BOM- MBC Sightings by Town, 1991-2013

In western Massachusetts, Harris’ has been reported from Florida, Savoy, Rowe, Heath, Windsor, Plainfield, and Shelburne in the north, but from only one central or south Berkshire town, Stockbridge (2, 6/16/1997, D. Potter). Other than that, from the southern Berkshires there is only one suspect report of an out-of-flight-period individual on the 7/27/1996 NABA Count, Sheffield. All of these western reports are of quite low numbers. In the Connecticut River valley there are reports of singles from Amherst and East Longmeadow, but from no other towns, and this species is rare in “the valley.”

The greatest concentrations of Harris’ Checkerspot are in central Massachusetts (see locations below).

In southeastern Massachusetts, the 1986-90 Atlas had one record: New Bedford (Bristol County) (2, 6/15/1988, M. Mello). This was from the Acushnet White Cedar Swamp area, which was not been checked again after 1988 (M. Mello, pers. com.), but was searched on 6/8/2011 by S. and J. Stichter, who did not find any evidence of Harris' Checkerspot or its host plant. For 1991-2013 MBC has Bristol County reports only from Easton (e.g. 6/16/1995, 50, B. Cassie), a town which is much further north; it is the southernmost town shown on Map 46. There are no reports of Harris' from Cape Cod (Mello and Hansen 2004). In sum, Harris’ Checkerspot may well be gone from the southeast coastal plain of Massachusetts, and is absent from the Cape and islands.

In Essex County north of Boston, numbers are small. The MAS Atlas had reports from Ipswich, Lynnfield and North Andover. MBC records also report the North Andover colony (at Weir Hill TTOR), and add small colonies in Newbury (Martin Burns WMA) and Groveland (Crane Pond WMA). The Atlas reports from Ipswich, Lynnfield, and especially from Boston West Roxbury Highland Park, all need to be re-confirmed, since the species may well have retreated from these areas in the last twenty years.

Locations from which Harris’ Checkerspot has been reported in good numbers between 1991 and 2013 include

Southeast: Easton max 50 on 6/16/2005 B. Cassie.

Essex County: Groveland Crane Pond WMA max 6 on 7/3/2003 S. Stichter; Newbury Martin Burns WMA max 22 on 6/28/2003 S. Stichter and D. Savich, 4 on 6/19/2011 S. Stichter and T. Whelan; North Andover Weir Hill TTOR max 21 on 6/6/2009 H. Hoople.

Worcester Co.: Hubbardston Barre Falls Dam SP max 37 on 6/19/1999 T. and C. Dodd, recent max 11 on 6/23/2005 D. Price, E. Barry, J. Mullen; Lancaster Ballard Hill Recreation Area max 10 on 6/15/2004 T. Murray; Milford power line max. 48 on 6/11/1994, R. Hildreth, and Rt. 85 power line max 13 on 6/8/2001 R. Hildreth; Petersham North Common Meadow TTOR max 22 on 6/26/2005 E. Nielsen, 12 on 6/20/2011, G. Breed and P. Severns (and more on privately owned parcels in Petersham); Princeton Wachusett Meadow WS max 24 on 7/1/2007 Nor. Worc. NABA, but declining numbers since; Royalston Tully Dam max 10 on 6/26/2005 C. Kamp; and Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS max 44 on 6/12/2004 B., R., and M. Walker.

The following four colonies have been monitored:

At MassAudubon’s Broad Meadow Brook WS in Worcester, Harris’ Checkerspot occurs in two areas along a power line. Since 1991, yearly counts ranging from 2 to 44 adult butterflies have been made. Beginning in 2005, MassAudubon and the utility company supplemented spot herbiciding with mowing of a large part of the Harris’ habitat, since shrubs were encroaching. Results in 2006 and 2007, with high counts of 29 and 19 adults respectively, indicated that the butterfly population survived this mowing (Gach 2008). A biennial November mowing regime was then followed, and the area was mowed again in 2007 and 2009. 2010 was a poor year for Harris’ at most monitored locations, and no June adults were seen at Broad Meadow Brook, although 2 larval webs were discovered late in the fall, and a few adults appeared in 2011 (M. Gach, pers. comm). Finally, 9 were found on 5/30/2012 M. Gach (deGraaf and Cloutier photos), and 3 on 6/2/2013 G. Kessler (photos). Thus, counts of spring post-diapause larvae, flying adults, and fall larval webs through 2013 indicate that the population is persisting.

At the Trustees of Reservations’ Weir Hill property in North Andover, a wet meadow containing both Harris’ Checkerspot and Baltimore Checkerspot is mowed annually in late fall. The Galerucella beetle has been released to control purple loosestrife (Hopping 2009). The yearly high counts since 2004 at this site have been 20 on 6/10/2004 S. and J. Stichter; 15 on 6/11/2008 H. Hoople; 21 on 6/6/2009 H. Hoople; 3 on 7/4/2010 H. Hoople (The year 2010 was a late and poor year for Harris’ at this and other locations); 7 on 6/13/2011 (plus 330 eggs photographed on 6/13/2011), H. Hoople; 7 on 5/28/2012 H. Hoople (photos); and 4 on 6/9/2013, R. Hopping.

At North Common Meadow TTOR in Petersham, yearly high counts of adults indicate some decline since 2004. The high counts were 16 on 6/15/2004 R. and S. Cloutier; 22 on 6/26/2005 E. Nielsen; 1 on 7/5/2006 R. and S. Cloutier; 8 on 6/12/2007 F. Model; 6 on 6/28/2008; no report 2009; 6 on 6/8/2010 B. Zaremba; 12 adults reported 6/9/2011 by G. Breed (and 150 larvae 5/19/2011) ; 3 on 6/23/2012 T. Gagnon +MBC; 5 larvae on 5/22/2013 T. Gagnon + MBC .

The situation at WTAG radio towers in Holden is a sad example of what can happen to a Harris’ colony through butterfly-unfriendly mowing practices (Stichter 2008). This large colony was discovered by Tom Dodd in the early 1990’s, and was visited almost yearly for many years. High counts were

|

Number Seen |

Year |

Date |

Observer |

|

30 |

1991 |

6/16 |

T. Dodd |

|

162 |

1992 |

6/20 |

T. Dodd |

|

178 |

1993 |

6/19 |

T. Dodd |

|

65 |

1994 |

6/18 |

T. Dodd |

|

200 |

1995 |

6/18 |

T. Dodd |

|

92 |

1996 |

6/15 |

T. + C. Dodd |

|

37 |

1999 |

6/13 |

T. + C. Dodd |

|

20 |

2002 |

6/10 |

T. Moore |

|

2 larvae |

2011 |

6/5 |

S. +J. Stichter |

At first the field was mowed once in late fall “whenever they got around to it.” Later, management became more intensive and mowing was done at the wrong times. The numbers of Harris’ Checkerspots plummeted. From 2002 through 2010 there were no reports, but in 2011 two late-stage larvae were found by S. and J. Stichter, indicating that the species persists but in much diminished numbers.

According to 1992-2008 MBC records, Harris’ Checkerspot has a short flight period, with nearly all sightings taking place in June or the first week of July (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp). It has only one brood each year. Peak flight time is the last three weeks of June. The NABA July Counts usually catch only the tail end of the flight period.

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records (1991-2013), the six earliest "first sightings" are 5/25/2010 North Andover Weir Hill, H. Hoople; 5/25/1998 Savoy, D. Potter; 5/26/2000 Worcester Broad Meadow Brook, G. Howe; 5/28/2012 North Andover Weir Hill, H. Hoople; 5/29/2006 Newbury, S. Moore and B. Volkle; and 5/30/2009, North Andover Weir Hill, H. Hoople. The particularly warm springs of 2010 and 2012 added to the early records. Thus 6 out of 23 "first sightings" have been in the last week of May. The next nine "first sightings" have been the first week in June (6/1 - 6/7).

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years of records, the four latest "last sightings" are 7/14/1996, Princeton, T. Dodd; 7/12/1995 Savoy, D. Potter; 7/11/2008 Sherborn power line, B. Bowker; and 7/3/2003 Worcester G. Howe and Newbury, T. Whelan. The Atlas late date was 7/15.

Scudder (1889:681-2) wrote that Harris' Checkerspot “appears on the wing about the middle of June, continues to emerge until the end of the first week in July and flies until the first of August.” Unless Scudder’s dates are based only on northern New England sites, today’s first sighting dates are considerably earlier, suggesting advancement in flight dates due to warming climate. Scudder’s assertion that it flies until August is surprising since today's flight in Massachusetts ends considerably earlier.

Harris’ Checkerspot should be on a “watch list” for Massachusetts. We include it here as a Species of Conservation Concern.

This species is univoltine, is dependent on a single host plant (monophageous), experiences high larval mortality, and apparently does not disperse great distances. These life history traits alone go far toward explaining its vulnerability, but in addition its northerly distribution in eastern North America makes it strongly susceptible to climate warming (Table 6; Breed et al. 2012). This is a relatively fragile species in Massachusetts..

The NatureServe website ranks Harris' Checkerspot as S1 or "critically imperilled" in Virginia, S2 or "imperilled" in West Virginia and Indiana, S3 or "vulnerable" in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, and SH or "possibly extirpated" in Connecticut (NatureServe 1/2014).

But these rankings may not be entirely up-to-date. Back in 2008, John Shuey, lepidopterist at The Nature Conservancy, remarked for Indiana that “...no one has seen Chlosyne harrisii in Indiana in decades; it may well be extirpated despite its S2 ranking....(Shuey 2008).”

The examples of Indiana, and Connecticut to our south, should spur Massachusetts to do more to locate, monitor and conserve colonies of this species.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-15-2014

Species of Conservation Concern

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS