ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

54 Milbert’s Tortoiseshell Aglais [Nymphalis] milberti (Godart, 1819)

The brillantly marked Milbert’s Tortoiseshell is always a delight. Its presence in Massachusetts is usually an incursion from the north, and, like the Compton Tortoiseshell, is somewhat unpredictable from year to year.

By the mid-nineteenth century much was already known about Milbert’s Tortoiseshell. Its New England status was summed up by Thaddeus W. Harris: “This showy butterfly is rare in the vicinity of Boston, but abundant in the northwestern part of the state and in New Hampshire. It appears in May, and again in July and August. The caterpillars live together on the common nettle (1862: 302-3, Fig 125; Index).” Harris had two July 3, 1835 specimens from Mr. Leonard in Dublin, N. H.

Photo: Northampton Community Gardens, F. Model, July 10, 2004

“Abundant” was probably an overstatement for northwestern Massachusetts. Scudder was more circumspect, saying Milbert’s was “a rather common species in Williamstown and some other parts of Berkshire Co., Mass.,” but even more common in northern New England. Most especially Scudder found it in the White Mountains, where it was “plentiful ... flying to the highest summits (1899: 425).”

Throughout both northern and southern New England in the nineteenth century, this butterfly benefited from the spread of non-native nettles along newly-cleared roadsides, and from the planting of lilacs near farmsteads. Scudder describes nectaring on spring lilacs, and June egg-laying on roadside nettles in Scarboro, Maine, noting that the host was “the common nettle” Urtica dioica, but also the native Urtica gracilis, with numerous larvae often swarming over the plants and stripping them of their leaves. “The caterpillars are sometimes so abundant in certain places that the nettles by the roadside are fairly black with them (1899: 425-7).”

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell is among those butterfly species which probably increased in numbers with the cutting of forests and the onset of European settlement and agriculture (Table 1). Other species which benefited from the increase in stinging nettles along roadsides and around farms are Red Admiral, Question Mark, and Eastern Comma.

Even so, Milbert’s Tortoiseshell’s presence in Massachusetts was probably somewhat sporadic, in contrast to areas further north. The decent numbers of Massachusetts museum specimens from the turn of the century probably reflect collectors’ interest in this striking and unusual butterfly. Scudder refers to an early specimen from Taunton (no date). Older literature reports singles found in Boston in 1874 and in 1907, and F. H. Sprague caught a specimen in Wollaston (now Quincy) in October 1877 (Psyche Vol I (1874): 4; Vol II (1879): 258; and Vol XIV (1907): 62). The Harvard MCZ has August-September 1883 specimens from Cambridge (4, F. H. Sprague) and from Mt. Toby in Sunderland (1, 8/31/1883, no coll.). There are early 20th century specimens from Weston (1918) and Tyngsboro (1918) (MCZ); Melrose (1917) (Yale); as well as Princeton (1908 or 1909, L. W. Swett), Great Barrington (1905-1919, C. W. Johnson), Framingham (1908, C. A. Frost), and Bristol R. I. (1911, H. L. Clark) (Boston University).

For the 1930’s and 1940’s, Farquhar (1934) and Root and Farquhar (1942) add specimens collected from the towns of Gilbertville, Salem, Marblehead, and Stoneham. But unlike Compton Tortoiseshell, Milbert’s Tortoiseshell does not seem to have made it to Nantucket or Martha’s Vineyard. There are no historical records (Jones and Kimball 1943; LoPresti 2011).

From the 1960’s through the 1980’s, Milbert’s Tortoiseshell seems to have remained an interesting if rather unusual find. There are specimens noted from Mt. Greylock (1964, Yale, no coll.), as well as Lenox (1959), Pittsfield (1967), and West Newbury (1979), where it was reported as “numerous,” in what appears to have been a one-time outbreak (LepSocSeasSum, 1960-1987).

Host Plants and Habitat

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell is among the “Switchers” listed in Table 3 ; it is one of the many butterflies which have adopted one or more non-native plants as larval hosts. European Nettles (Urtica dioica) is a plant which has sprung up around human settlement sites in Europe since pre-historic times, and indeed is used as an indicator of human disturbance by paleoarcheologists. As this plant came to the New World along with Europeans, it spread rapidly in disturbed soils, growing quite vigorously in comparison to New World nettle species, and with shorter senescence time. Milbert’s Tortoiseshell apparently quite quickly adopted this widespread new food source, thriving accordingly.

All species of Urtica are utilized. Photographs of Milbert's Tortoiseshell larvae found in the wild on what appears to be Urtica dioica are posted at www.massbutterflies.org (7/19/2003, Lexington; 6//6/2004, Harvard). Urtica gracilis and U. procera are native plants which probably also function as hosts. Closely related plants have not been reported as hosts, except that Wood Nettle, Laportea canadensis, is utilized under laboratory conditions (Scott 1986).

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell’s habitat is moist pastures, fields, and rural roadsides adjacent to woodlands; wet areas with nettles must be fairly nearby (Opler and Krizek 1984: 158). Adults take nectar from a variety of floral sources, and are more attracted to nectar than are Compton Tortoiseshells and Mourning Cloaks, the two most closely related species. Sap is utilized occasionally.

NatureServe (2012) notes that this is a mobile species within its northern range; it may utilize almost any patch of nettles in various kinds of habitats. It also seems to gravitate to higher elevations: Opler and Krizek (1984) note that Milbert’s is a higher-elevation species in Colorado, but that the adults in alpine environments seem to be seasonal migrants from lower elevations, arriving to nectar but returning to lower elevations where their host plant occurs to lay eggs and to hibernate.

Relative Abundance Today

The number of MBC sightings 2000-2007 rank Milbert’s Tortoiseshell as Uncommon in the state (Table 5). It was seen slightly more frequently than the Compton Tortoiseshell. The total number of 1986-90 Atlas reports also ranks Milbert’s Tortoiseshell as Uncommon, but for some reason the Atlas chose to label it “locally common.” MBC records 1992-2011 do not contain any reports of sites where Milbert’s Tortoiseshell was “common” over several seasons, except perhaps Mount Greylock. In all other cases high numbers seen were the result of outbreaks which did not persist beyond one year.

Chart 54: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

What jumps out from Chart 54 is the large incursion and subsequent outbreak of Milbert’s Tortoiseshell in 2003 – 2005, which peaked in 2004. While Milbert’s is usually seen only in ones or twos from a single location, in 2004 large numbers were reported from many locations across the western and central parts of the state. The story is perhaps best told from the counts on Mount Greylock, where only 1 to 4 were reported annually in the years prior to and following 2004, but a total of 62 was counted on 6/12/2004 by M. Lynch and S. Carroll, and double-digits by other observers that year. The numbers found on the Northampton NABA Count over the years also illustrate the outbreak: whereas counts of Milbert’s’ were 4 in 2003 and 0-15 in 2006-8, 176 were counted in 2004, and 105 in 2005.

The only other year with an especially large number of reports, and a few large concentrations, was 1999. There are no reports at all from 1992, 1996 or 2002, years which there were many butterfly field trips and reports of other species, so Milbert’s numbers were presumably very low those years. Although not shown on the chart, 2010 was similar to 2009 in terms of numbers of sightings. But, as with Compton Tortoiseshell, 2011, 2012 and 2013 were poor years for Milbert's in Massachusetts: only 4 were reported in 2011 and 5 in 2012, from northerly locations, and none at all reported in 2013.

No two-decade trend in Milbert's sightings can be deduced from Chart 54, and the Breed et al. 2012 list-length study did not include Milbert's because of the small numbers of reports.

Although Milbert’s Tortoiseshell has been seen at many locations over the years, there is a lack of known colonies which persist from year to year. This suggests that most Massachusetts sightings are the result of periodic dispersions from further north, which establish temporary breeding populations but probably do not persist for very many years (Cassie 2004).

State Distribution and Locations

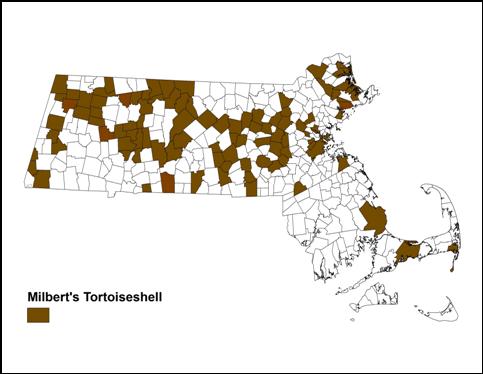

Wandering Milbert’s Tortoiseshells could turn up in almost any part of the state, but they are much less common in southeastern Massachusetts and Cape Cod than further north, and in fact they have never been found on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket (Pelikan 2002; LoPresti 2011). The 1986-90 Atlas did not find Milbert’s at all in southeastern Massachusetts or the islands. BOM-MBC records (Map 54) show three reports from the southeast (one each from Plymouth, Barnstable, and Chatham, of one or 2 individuals each), but a preponderance of reports from the north and west.

Map 54: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

In the 22 years 1992-2013 Milbert’s Tortoiseshell was seen in 96 of the 351 towns in the state.

Northwestern Massachusetts is usually thought of as within the “normal” range of this butterfly, but temporary colonisation may be the norm there as well as further southeast. The butterfly has been seen fairly regularly (almost every year), in Williamstown and on Mt. Greylock, but it is surprisingly scarce on the Berkshire NABA Counts. The Northern Berkshire NABA Count has been in existence for 21 years, 1993-2013, yet Milbert’s has been reported in only 5 of those years: 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009, and 2011. The Central Berkshire Count, based in Pittsfield, has been in existence for 24 years, 1986-2011, and Milbert’s has been reported in only 4 years: 1997, 2003, 2004, and 2009. Milbert’s has been found only three times on the Southern Berkshire NABA Count.

Milbert’s Tortoiseshells are usually seen only in ones or twos. The following locations have had either larger numbers or multi-year reports:

Adams/New Ashford Mount Greylock, max. 62 on 6/12/2004, M. Lynch and S. Carroll, recent max. 5 on 6/4/2010 K. Wallstrom; Adams Greylock Glen max. 3 on 7/17/2004, E. Nielsen; Amherst South max. 9 on 7/20/2004, M. Faherty; Egremont Jug End Res., max. 2 on 6/13/2004, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; Erving Millers Falls, max. 13 on 7/10/1999, C. Franklin NABA; Grafton Dauphinais Park, max. 8 on 6/12/2004, D. Price et al.; Harvard Oxbow NWR, max. 36 on 8/3/2003, T. Murray; Heath, max. 2 on 8/2/1998, D. Potter; Hubbardston MDC property, max. 5 on 6/20/2001, D. Small; Lenox Geo. L. Darey WMA, max. 4 on 8/8/2004, E. Nielsen; Lexington Dunback Meadows, max 12 on 7/13/1999 and 10 on 7/16/2003, M. Rines; Northbridge Larkin Rec. Area, max. 4 on 9/5/2003 R. Hildreth; Northampton community gardens, max. 8 on7/16/2004 T. Gagnon; Royalston, max. 4 on 8/2/2004, C. Kamp; Warwick, max. 3 on 6/23/2003, S. Heinricher; Williamstown, Mountain Meadow Preserve, max. 2 on 7/21/2005, P. Weatherbee.

Broods and Flight Period

A percentage of Milbert’s Tortoiseshells overwinter as adults (estivate), and these often emerge quite early in spring, like the Mourning Cloak. This accounts for some quite early sightings in March and even February. Some Milbert’s, however, do overwinter as chrysalids, and these probably emerge in April, with “both new and old” adults flying until the end of May (Scudder 1899: 427). Thus, the first flight period for Milbert’s Tortoiseshell is late-March through May, and this flight is clearly visible in the MBC flight chart http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp .

After spring arrival or emergence in Massachusetts, Milbert’s probably produces two or three more generations here that season. The second generation flies about mid-June through early August, and is also quite visible in the MBC flight chart. Scudder describes it thus: first flight adults “lay their eggs on the young nettles late in April and in May, and the caterpillars begin to change to chrysalids in the first half of June; after passing from 10 to 12 days in this state, the first brood of butterflies from chrysalids of the same year makes its appearance, say about the middle of June, and becomes abundant by the 21st – at least in the southern portions of its range. The butterflies continue on the wing until after the middle of July...” (1899:427).

There is even a third brood, according to Scudder, which flies beginning at the end of July or in early August. Last-brood (extending to become the first brood of the following year) Milbert’s adults can appear as quickly as early September; this flight too is visible in the MBC flight chart. These are the adults which will hibernate over the winter and constitute the first flight of the next season. A portion of the final brood does not eclose and overwinters as chrysalids. Scudder thought there were three broods each year. But flight periods overlap, and September to March is counted as one flight period (1899: 427-8; also Opler and Krizek 1984: 289).

Earliest sightings: In the 22 years of BOM-MBC records 1992-2013, the four earliest "first sighting" reports are 2/6/2000 Athol, D. Small [an unusually early date]; 3/22/2005 Charlemont, J. Strules; 3/26/1999 Pittsfield Canoe Meadows WS, T. Tyning; 3/26/2004 Paxton, E. Barry and 3/26/2004 Sunderland D. Case. The boom year of 2004 thus started with two sightings in March, in different locations. The 1986-90 Atlas cites an even earlier date: 3/3/1984, Millis, B. Cassie.

Latest sightings: In the same 22 years of records, the seven latest "last sightings" are 10/27/2000, Boylston Tower Hill K. Haviland; 10/25/1998 Heath, D. Potter; 10/25/2003, Warwick, S. Heinricher; 10/18/1994 Princeton, B. Van Dusen; 10/13/2010, Shelburne Falls, J. Boettner; 10/12/1997 Foxboro, M. Champagne; 10/9/2011 Beverly, M. Arey; and 10/9/2006 Chatham, F. Model. In eleven out of the 22 years under review (1992-2013), the latest sighting has been in October.

There are usually only small numbers of adults seen during September and October (MBC flight chart). Scudder says the butterfly “may occasionally be found even to the middle of November” but no November sightings have been reported in recent years..

Outlook

Older range maps (e.g. Opler and Krizek 1984) show all of Massachusetts as within the normal range of Milbert’s Tortoiseshell. These are not accurate; the species is not and never was consistently found in southeastern Massachusetts. More recent maps (e.g. Cech and Tudor 2005) show only northwestern Massachusetts as within the normal range. Milbert’s may be becoming uncommon now even in northwestern Massachusetts.

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell could easily contract its range northward as a consequence of climate warming in the northeast. Already sporadic and uncommon here at the southern edge of its range, it may become more so in the future. Milbert’s is therefore added to the list of butterfly species in Table 6 which may be expected to withdraw northward as climate warms.

The 1995-99 Connecticut Atlas found only one vouchered specimen, compared to 29 specimens from pre-project years, suggesting some decline in that state (O’Donnell et al. 2007). The species is probably extirpated in New Jersey (NatureServe 2012); local writers calling it “another species retreating northward (Gochfeld and Burger 1997: 194).”

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell is among those species for which traditional conservation measures like habitat management may not be enough to prevent decline. There is already a good amount of suitable habitat available, although this species, like the Early Hairstreak, should alert us to the importance of conserving and protecting high-elevation mountain sites. And at any elevation planting and encouraging nettles -- rather than eliminating them -- in backyards and conservation areas would help this and other butterfly species.

© Sharon Stichter 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 1-20-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS