ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

13 Harvester Feniseca tarquinius (Fabricius, 1793)

Harvesters in New England were first reported by Scudder in 1862, from specimens found by collectors in Maine and New Hampshire. Up to this time, tarquinius had been known to Scudder only from the southern states; the butterfly had been figured by John Abbot in Boisduval and Le Conte (1829- [1837]), but had been named even earlier by Fabricius from a specimen now probably lost (Miller and Brown, 1981: 92; Calhoun 2004). Scudder (1862) at first maintained that the New England specimens were different from the southern tarquinius, but in his 1889 work he abandons that view. By that time he knows of four Massachusetts specimens of tarquinius, all from the southern part of the Connecticut River valley.

Photo: Windsor, Mass. July 12, 2012 F. Model

There are many 1880 – 1924 specimens of the Harvester butterfly at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology and at Boston University. Specimens are from North Leverett, South Hadley, Deerfield, Granby and Springfield in the Connecticut River valley; from Great Barringon in Berkshire County and Southbridge in Worcester County (BU: C. W. Johnson; also listed for Worcester by Forbes 1909); as well as from Malden, Clifton, Boston, Cambridge, Wollaston, Waltham, Reading (Maynard 1886), Weston, Lincoln, Tyngsboro, Framingham and Auburndale in eastern Massachusetts.

Harvesters were probably not rare in turn-of-the-century New England -- simply uncommon, mobile from year to year, and confined to the edges of wetlands. But many naturalists like Maynard and even Scudder thought they were rare. They were certainly somewhat negatively affected by the loss of wetlands due to agricultural and industrial development. A. H. Clark collected actively in eastern Massachusetts at this time, but lamented that he had never been able to capture a Harvester. Finally, “I noticed, on July 25, 1910, a single specimen flying low over the lawn of the house at the southwest corner of the intersection of Lowell and Highland Avenues, Newtonville. Seizing the hat from the head of a child which was playing near by, I succeeded, with this substitute for a net, in capturing it” (Clark, 1913). Today, the Harvester is no doubt gone from Newtonville, owing to dense urban development, but can still be found in other locations not far from Boston.

A few years later Clark made a special search for Harvesters, writing that “The summer of 1923 in eastern Massachusetts was noteworthy for....the abundance of Feniseca tarquinius in correlation with the unusual abundance of its host (Schizonneura tesselata),” whereas in 1924 the numbers of all butterflies including Feniseca were down. In 1923 he found several Harvester locations in Newton and Weston, including Newton Center, Newtonville, and West Newton, and also Essex and Manchester in Essex County (Clark 1925).

Farquhar’s 1934 summary of the state distribution of the Harvester adds only the northeastern towns of Middleton and Stoneham (Essex Co.; a C. V. Blackburn specimen is in the Furman University collection), and Gilbertville (Worcester Co.) to those already mentioned. Lepidopterists’ Society reports from the 1960’s add the locations of Topsfield (Essex Co.) in 1967, Longmeadow (Hampden Co., Fannie Stebbins WS) in 1974; Shutesbury (Franklin Co., larvae on wooly aphids on black alder) in 1976, and Shirley (Middlesex Co.) in 1989.

There are no early specimens of Harvester from southeastern (coastal plain) Massachusetts or the offshore islands, and still today it is not normally found in those regions. Jones and Kimball’s 1943 review of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket lepidoptera does not list Harvester, indicating that the species was not found on the islands historically.

Host Plants and Habitat

Unlike all other Massachusetts butterfly species, the Harvester’s larval host is not a plant, but rather several genera of aphids. Wooly Aphid (Prociphilus tessellates) may be the most common host (Wagner 2005). Harvester larvae are therefore carnivores: they feed on the aphids.

The adult butterfly imbibes from moist earth, carrion, dung, and the honeydew secreted by the aphids. The aphids in turn use several plant species, although the butterfly in Massachusetts has typically been found only on alder aphids. Cech emphasizes that some species of aphids shift between two tree hosts each year (Prociphilus, for example, shifts between alder and silver maple), and that the Harvesters must follow the aphids, laying their eggs on the aphid clusters (Cech 2004: 99). Aphid movement from bush to bush may explain why finding Harvesters can be difficult; Harvesters can appear and then disappear at a given location from year to year.

The Harvester is known to be sporadic or transient; it may easily colonize a location, die out, and then recolonize. Weed (1919) calls it “The Wanderer,” in recognition of its ability to follow the shifting locations of aphids. Dale Schweitzer maintains that sighting histories show Harvester to be a good long-distance colonizer, and that urban or agricultural areas separating suitable habitat do not seem to act as barriers to colonization (NatureServe, 2011).

Smooth and Speckled Alder (Alnus serrulata and Alnus incana), the hosts for the aphids, are native to and found in all counties in Massachusetts except Nantucket (Sorrie and Somers, 1999). Harvesters and their aphids have also been found using the introduced Black or European alder (Alnus glutinosa), for example along the Mystic River in Medford/Arlington. Harvester colonies, or their aphids, may prefer fairly large stands of alder. For example, in Fowl Meadow in Milton, Sam Jaffe reported finding seven large Harvester caterpillars between three small colonies of aphids, but while every patch of aphids had caterpillars, the aphids themselves were very sparse and present on only a small fraction of the available alders (Jaffe, masslep, 9/20/2009). The alder stands may also have to be associated with silver maple. Habitat types include forested wetland, scrub-shrub wetland, and riverine.

Scudder gives credit to a Miss Emily L. Morton of New York, to Misses Soule and Eliot, who summered at Stowe, Vt., and to Dr. Asa Fitch, for discovering that Harvester eggs are laid on aphids and that the larvae eat only aphids (Scudder 1889:1020). The association with alder in New England has been known since Scudder’s day.

Relative Abundance Today

MBC records rank Harvester as Uncommon today (Table 5); it is about on a par with Leonard's Skipper and Bronze Copper in terms of frequency of sightings. During the Atlas period, Harvester was found in 37 of 723 blocks, and the Atlas also ranked it as Uncommon.

Chart 13: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

In order to get a better picture of the status of Harvester state-wide, and to make possible comparisons with years prior to 2003, Chart 13 omits the reports from the large and well-reported Arlington/Medford colony. The chart shows that for the rest of the state there was a steady small number of Harvesters reported each year, with some yearly fluctuations. 1992 is unusual, since Harvesters were targeted for searches, and there was a much smaller number of total trips. From these data, there is little case to be made for either increase or decrease in the statewide non-Medford abundance or detection rate. However, a Breed et al. (2012) list-length analysis of MBC 1992-2010 data (including Medford) showed a statistically significant -22.1% decrease in detectibility of this species over that time period, probably mainly due to the inclusion of the 1992 data.

In 2003 a particularly large concentration of Harvesters was found in the Arlington and Medford Mystic Lakes area by Renee LaFontaine and Marj Rines. Here Harvesters are hosted by wooly aphids on large Black or European Alder (Alnus glutinosa) trees which were planted along the Mystic River basin and around the lakes. Silver Maple is also present as another aphid host. This flourishing Harvester colony has been visited every year since 2003, and the August high counts have been in the double-digits, with a maximum of 67 on 8/21/2008. LaFontaine and Rines reared a number of larvae from this colony, and showed that they over-wintered in the chrysalis form (LaFontaine and Rines 2006; www.mrines.com/butterflies/harvesters ). The pupal hibernation stage had not previously been shown for Massachusetts, but Schweitzer had shown it for larvae reared from Maine (Natureserve.org, 2010).

State Distribution and Locations

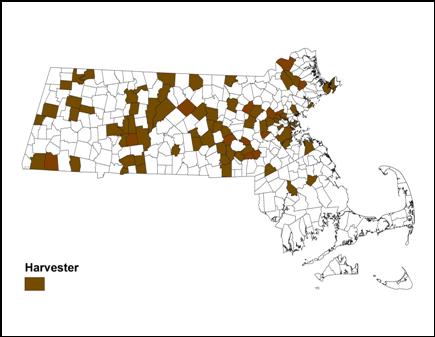

Harvester is not normally found in southeastern Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, or on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. The 1986-90 Atlas had no reports from these areas, and BOM-MBC records have very few. Between 1992 and 2013, Harvesters were found distributed in 75 towns across the state, according to BOM-MBC records (Map 13).

Map 13: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

Harvester is most frequently reported from central Massachusetts and from the Connecticut River valley, and has been rather hard to find in the Berkshires and, oddly, in Essex County today despite the many historical reports. The few recent reports are from Boxford, North Andover, Haverhill, and Gloucester.

The 1986-90 Atlas did not find Harvester in northern Berkshire County, but small numbers of Harvesters were reported on the Northern Berkshire NABA Count in 1995 and 1999, and from the Central Berkshire NABA Count in 2004 and 2008. Singles have been reported from the towns of Florida, Rowe, Windsor, Cummington and Peru.

MBC records show that Harvesters have been found as far southeast as Halifax in Plymouth County (2, 9/8/2001 M. Faherty) and Raynham in Bristol County (1, 5/31/1999 B. Cassie). These two reports extend the known range southward a bit from the earlier Atlas and BAMONA records. However, the Club still has no records from Barnstable, Dukes or Nantucket counties. Mello and Hansen (2004) do not report Harvester for Cape Cod, and Pelikan (2002) does not list it for Martha’s Vineyard.

With the exception of the Medford/Arlington concentration, Harvester numbers reported from any one site rarely exceed three.

Aside from the Harvesters to be found along the Mystic River and Lakes in Medford and Arlington, other consistent or recent locations for this species have been Longmeadow Fannie Stebbins WS (2, 8/21/2010 B. Zaremba; photos); Milton Fowl Meadow (4, 7/28/2012 M. Arey; Jaffe 2009); Wellesley Wellesley College (5, 9/1/2012, G. Kessler and G. Dysart, photos); Windsor Notchview TTOR (4, 7/13/2013, R. and S. Cloutier); Worcester Broad Meadow Brook WS ( 2, 7/29/2001, G. Howe, 1, 5/25/2006 T. Murray and B. Walker); Harvard Oxbow NWR (1, 5/29/2008, R. Hamburger); Holliston Patoma Park (7/10/2010, D. Willis); Concord Great Meadows NWR, 3 larvae 7/24/2012, G. Dysart, photos); Northbridge Larkin Recreation Area (1, 9/4/2009, B. Bowker); Petersham Tom Swamp (1, 5/23/2010 T. Gagnon et al.). In 2009 and 2010, photographer Sam Jaffe found small populations of Harvester at Great Black Swamp in Millis and Medway, Arnold Arboretum in Boston, and Great Meadows NWR in Concord (Jaffe 2009; 2010).

Broods and Flight Period

The Harvester is multi- brooded, with a fast cycle from egg to adult, and probably has from three to four generations a year in Massachusetts. Field observation by LaFontaine and Rines of the colony in Medford revealed three flight periods: a small flight in early-mid June, a larger one in mid-July, and a still larger one in mid-to-late August (LaFontaine and Rines 2006; also D. Willis reports three flights in Holliston, pers. comm. 7/2/2013). These three main flight periods are also somewhat evident in the statewide data shown at http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp , along with what seems to be a partial fourth flight in some years in October.

First sightings: In seven of the 23 years of MBC data (1991-2013), the first sighting of a Harvester has been in the first two weeks of May. These seven earliest reports are 5/2/1999 Northbridge Larkin RA, T. Dodd; 5/4/1991 no location, T. Dodd; 5/7/2010 Paxton, E. Barry; 5/11/1992 South Hadley, T. Fowler; 5/11/2004 Belchertown Quabbin Park, D. Small; 5/12/2012 Medford, R. LaFontaine and M. Rines; and 5/14/1995 Northbridge, R. Hildreth.

Last sightings: The largest numbers of Harvesters are usually found in August, with that flight ending in mid-September. But in some years a few Harvester have been found in October. In the 23 years of MBC data (1991-2013), there have been only two years with October-November reports: 23 October 1999 Milford, R. Hildreth and 9 October Brookfield, R. Hildreth, However, during the 1985-90 Atlas period there were three October-November reports: 6 November 1988 Millbury, T. Dodd (and 1 October 1988 Foxboro, B. Cassie); and 23 October 1987 Natick, E. Landre. The latest reported date for the Medford/Arlington colony is 24 September 2004, so an October flight has not been noted at that location except from a raised specimen (LaFontaine and Rines 2006).

The flight time of Harvesters may have advanced compared to 100 years ago: the spring emergence may be slightly earlier and the fourth October flight may be a new phenomenon. Scudder wrote that in New England the first flight was “the last week in May through mid-June,” the second early in July, and the third “about the middle of August, providing fresh specimens until near the end of September (1899: 1023).”

Outlook

Harvester colonies can appear and disappear frequently from known locations, so that this butterfly can be difficult to monitor. Natureserve (2011) lists Harvester’s status in Massachusetts as S3S4: somewhere between “vulnerable” and “apparently secure,” but this status should be reviewed. Harvester will probably not be negatively affected by climate warming in Massachusetts. The main threat is more likely to be the ongoing loss of wetlands in the state. A representative sample of known occurrences of this butterfly species should be monitored each year, and conserved alder swamps surveyed every few years for new colonies.

© Sharon Stichter 2012, 2013

page updated 11-30-2013

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS