ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

26 Frosted Elfin Callophrys irus (Godart, 1824)

Frosted Elfin is state-listed as a species of conservation concern. Populations using Baptisia or wild indigo as a host plant are not rare in Massachusetts today, because climate warming, habitat restoration and more search effort have resulted in an increase. But populations using Lupinus perennis or wild lupine remain rare: only three are known, all in the Connecticut River valley and all associated with airports.

Frosted Elfin, Hoary Elfin, and Henry’s Elfin were confused by early lepidopterists. Scudder and others in the nineteenth century, such as Godart, described something called Incisalia irus, but the descriptions and host plants often applied to Henry’s and Hoary, rather than (or as well as) to Frosted. Recently it has been shown that Scudder’s descriptions of the larva, pupa, and larval host plants of C. irus actually refer to C henrici; Scudder’s figures are reproduced from Abbot’s drawings of C. henrici in Boisduval and Le Conte (1829-{1837}) (Calhoun 2004; see Henry’s Elfin species account).

Photo: Weir Hill, North Andover, Mass. H. Hoople, June 5, 2007

As a result of early confusion, we know hardly anything about the abundance or distribution of Frosted (or Henry’s or Hoary) Elfin in Massachusetts in the nineteenth century, except that all three species were thought of as rare. Scudder’s oft-cited report of I. irus on Nantucket could actually have referred to Hoary or Henry’s or Frosted Elfin (Scudder 1889: 839). Even as late as the 1930s, Farquhar still says for New England that Frosted Elfin “is so generally confused with henrici and polios [Hoary] that records are not trustworthy.” However, he believed that Frosted “had been taken in several localities in east and central Massachusetts (Farquhar 1934).”

With the benefit of present-day knowledge, most museum specimens have now been re-classified to the right species, and it appears that Frosted Elfin was rare in eastern Massachusetts prior to 1900, but fairly easy to find between 1900 and 1990. We examined a large dataset of Massachusetts elfin specimens from most major museums, including the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) at Harvard, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Smithsonian, the McGuire Center at the University of Florida, Yale Peabody, Boston University (BU), and University of New Hampshire (UNH). Also included are all Lepidopterists’ Society Season Summary and Correspondence (LSSSC) reports, supplied courtesy of Mark Mello. These data were compiled in 2010 by a lycaenid and climate change working group at Boston University led by Dr. Richard Primack, and were kindly made available by him.

The only Frosted Elfin specimens prior to 1900 are one from Wellesley (9 May 1890, A.P. Morse) and two from Waltham (6 and 15 May 1897, C. Bullard), all in the MCZ. Since collectors were active 1870 to 1900 in many areas of the state, including Cape Cod, Springfield and Amherst, but not the Montague area, Frosted Elfin does appear to have been fairly rare at this time, at least in the east.

But between 1901 and 1950 there are Frosted Elfin specimens from many eastern Massachusetts towns: Barnstable (1950), Brewster (1919), Harwich (n.d.), Pepperell (1929), Tyngsboro (1919), Walpole (1930), Wellesley (1931) and Weston (1920) in the MCZ and at Cornell; Fall River and Middleboro in the 1930s and 1940s at AMNH, UNH and the McGuire Center; Eastham (1932) at BU; Bourne (1936) at the McGuire Center; and Westport (1941), Somerset (1941), and Waquoit Bay (1934) in the Yale Museum. In some cases there many individual specimens from one place (e.g. Barnstable). The only eastern region not represented is Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket (Jones and Kimball 1943). A butterfly found in so many areas cannot be said to have been rare, even if a few of these specimens may still be misidentified.

From 1951 to 1990, specimens labeled Frosted Elfin exist from an additional list of towns. In particular, the earliest specimens of the lupine-feeders in western Massachusetts are from the early 1970s, when the Montague Plains area in Franklin County was visited. In 1973, lepidopterist Frank D. Fee worked with various elfin species in Montague and reported Frosted Elfin associated with lupine at that location (LSSS 1973; specimen from Fee, May 16, 1974, McGuire). In 1964, J. D. Turner found Frosted Elfin in Sherborn (specimen May 10, McGuire). In 1974 Frosted Elfin was discovered in Medfield in eastern Massachusetts by William D. Winter (specimen in MCZ), and Willis found some in the Holliston-Framingham area (possibly at Sherborn power line cut) (LSSS 1974). Specimens exist from North Dartmouth (1986, Mello); Plymouth (1984, Myles Standish, D. Schweitzer, McGuire); Wilmington (1986ff, R. Godefroi, McGuire), and Rowley, Woburn, and Wareham (all 1975, Smithsonian, R. Robbins).

In light of these data, Frosted Elfin is placed on Table 2 as a species which may have increased between 1900 and 2000, at least in eastern Massachusetts. It may have benefited from limited anthropogenic disturbance such as forest clearing and fires on sandy soils and hilltop barrens. But since about 1950, increased and seemingly unrelenting development has probably decreased habitat for this species in both eastern and western Massachusetts.

Host Plants and Habitat

Massachusetts has two rather different populations of Frosted Elfin, the populations in eastern Massachusetts which feed solely on wild indigo or Baptisia tinctoria, and those in the Connecticut River valley which utilize wild lupine or Lupinus perennis. There is speculation among lepidopterists that populations feeding on these two different plants may be different races or subspecies (Schweitzer 1992). Throughout the Frosted Elfin’s range, there are some morphological differences between the two populations, among both adults and larvae, and apparently no females oviposit on both plants, even at those few locations where the plants co-occur (Schweitzer et al. 2011: 165) The lupine-feeding populations feed on flowers and seed pods, as well as leaves; for photos by Prof. Ernest Williams of lupine feeding behavior, see http://academics.hamilton.edu/biology/ewilliam/irus/default.html. The Baptisia populations seem to feed only on leaves and stems. There are said to be flight time differences, with lupine-feeders flying earlier, although the BOM-MBC database is not large enough for this to be demonstrable for Massachusetts.

There is a habitat difference as well. While both the lupine and the Baptisia can occur on sandy soil---such as that at Montague Plains or on the southeast coastal plain---Baptisia-feeding populations can also occur on rocky outcrops and glacial till, such as those occurring on drumlins north of Boston. Both areas are sometimes described as heath or grass openings in pitch-pine scrub oak ‘barrens.’ But a certain amount of tree cover is critical for the Baptisia-feeding populations (Albanese et. al. 2007a, 2007c), whereas the lupine-feeding populations seem to need more open areas.

Both habitats are somewhat disturbance-dependent. In the past disturbance was provided by natural fire or wind blowdown, but in historic times disturbance has been primarily anthropogenic.. Hence we find Frosted Elfins on power line cuts, rail lines, old sand/gravel pits, and airports. Maintenance of the habitat usually involves further mowing, fire, brush cutting or herbiciding to keep it open (e.g. Hopping 2009). Not all anthropogenic habitats with the food plant are suitable: highway shoulders with the food plant are generally not used by Frosteds, because mowing at the wrong time kills the larvae and because the wind and pollution may drive off adults. Habitats range from small to large in size. Frosted Elfins are not highly mobile; they are usually not found more than 20 meters from their food plant, and it is not known how well they disperse. Both lupine and Baptisia feeders do tolerate late summer or dormant season mowing every 1 to 4 years (NatureServe 2010).

The use of fire to manage Frosted Elfin sites is controversial, and lupine and Baptisia feeders differ in this respect. Lepidopterist Dale Schweitzer argues that the pupae of lupine-feeders spend most of the year a centimeter or so below the soil surface and therefore to some extent survive fires (Schweitzer et al. 2011: 166). Although adults will leave an area after burning, this is probably due to short-term loss of nectar, and historically they have re-colonized burned areas. Even so, tree removal is a technique which is less hazardous to pupae, and in one well-documented case in the Rome, N. Y. sand plains, plant and butterfly response was quick and positive (Pfitsch and Williams 2009).

Baptisia feeders, on the other hand, are not fire-adapted. Their pupae are found not underground but on the surface litter, and will not survive fires. Therefore, burning does not favor this species, but is lethal to it in the short run; thus only a portion of an actively used habitat should be burned each year (NatureServe 2010).

Four sites in southeastern Massachusetts (Lamson Road Foxboro, Myles Standish SF Plymouth, Noquochoke WMA Dartmouth, and Crane WMA Falmouth) were the locus of an intensive study by G. Albanese in 2004-6 to further specify the habitat characteristics of Baptisia-feeding Frosted Elfins. The adult elfin densities were greatest when the host plant density was greater than 2.6 plants per square meter, and when tree canopy cover was less that 29% but greater than 16%. In addition, even small quantities of non-native shrub cover negatively affected elfin densities, and it was recommended that these be removed (Albanese et al., 2007a).

Frosted Elfin larvae occurred more often on Baptisia plants of large size, under moderate tree canopy cover, and it was hypothesized that canopy cover may improve host plant quality and/or protect larvae from predators. Females actually laid eggs on plants of all sizes and under varying canopy conditions, but larval survival was greatest under the optimal conditions (Albanese et al, 2007c). Albanese also demonstrated stem feeding behavior on Baptisia plants, and observed the frequent association of larvae with several species of ants. The ants may protect them from predators and parasitoids (Albanese et al, 2007b).

Relative Abundance and Trend Today

The 1986-90 Atlas found Frosted Elfin in only 12 of 723 blocs searched, making it “Rare” in the state at that time. Although known from the 1970’s from the Montague Plain/Turners Falls area in Franklin County, it was not found there during the Atlas period, probably because the population was at a low (M. Nelson, pers. com. 2/25/2011; M. Fairbrother, pers. com. 7/14/2010). Veteran local butterfly observer Mark Fairbrother re-located Frosted Elfins there a few years later (e.g. an estimated 30 at Montague on 5/9/1993, MBC records).

Since the Atlas years, there has been an increase in the numbers of Frosted Elfins seen, and today, according to 2000-2007 MBC records, the species ranks as Uncommon-to-Common (Table 5). The sighting frequency (at the proper time and location, of course) is about on a par with Brown Elfin and Eastern Pine Elfin. MBC records reflect primarily the eastern half of the state.

The dramatic increase in Frosted Elfin sightings per trip between 2000 and 2007 can be seen in Chart 26. In a few cases, for example at Weir Hill in North Andover and Turners Falls airport, new habitat has been created through informed management, and to some extent observers may have been looking more diligently for this species, but in large part the numbers seen are from locations which were being visited for other butterfly species, and from which Frosted Elfin had not been known before. Such new locations include Acton Fort Pond Brook, Barnstable Marstons Mills airport, Chelmsford power line, Edgartown Katama plains, Medford Middlesex Fells, and Woburn Horn Pond Mountain.. It thus seems probable that Frosted Elfin did actually expand its numbers in the state 2000-2007, particularly in eastern Massachusetts, followed by some decline in 2008 and 2009. In addition, list-length analysis of the same data by G. Breed et. al (2012) finds this same large increase (1000% between 1992 and 2010, statistically significant), and attributes it mainly to climate warming rather than habitat increase or increased search effort.

Chart 26: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

The high readings in 2005, 2006 and 2007, and the drop in 2008, are in part the result of an expanding population at the well-reported Lamson Road site in Foxboro (see below). Massachusetts Butterflies Season Summary statistics, also reflected in Chart 96, showed that the average number of Frosted Elfins seen on a trip in 2007 was up 415% compared to the average for preceding years back to 1994, but was down 62% in 2008, then back up 65% in 2009 (Nielsen 2008, 2009, 2010).

State Distribution and Localities

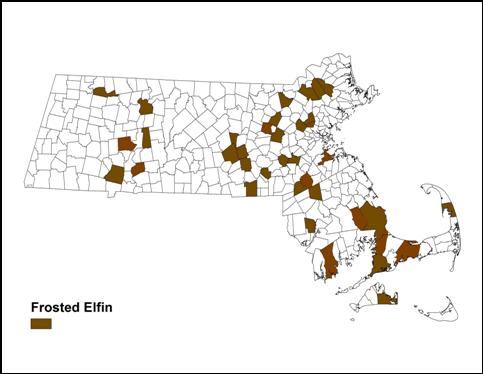

Frosted Elfin was reported from a total of 37 towns between 1992 and 2013 (Map 26). This is more towns than were found during the Atlas years, and more than are shown on the 2007 NHESP map (NHESP Fact Sheet, 6/2007). The towns found in the three databases are not exactly the same. The 1986-90 Atlas had reports from three towns where MBC has no current records: Medfield, Webster and Wilmington, and NHESP has records from one town which is not in the MBC database: Tewksbury (NHESP Fact Sheet 6/2007). Still, even if a few of the MBC or Atlas reports are misidentifications or occurrences that no longer exist, the evidence indicates that Frosted Elfin is fairly widespread in eastern Massachusetts.

Map 26: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

The three known lupine-feeding populations in the Connecticut River valley are in Chicopee (Westover Air Reserve Base), Westfield (Barnes Airport), and Montague (Turners Falls Airport). At the Chicopee Westover Base, Frosted Elfin was numerous on April 29, 2011, when 149 were counted, and many photographed, but only 18 were found on similar visits in 2012 and 2013. At Westfield Barnes Airport, the highest count was 35 on 4/24/2010, T. Gagnon, B. Higgins and C. Gentes, with smaller numbers in subsequent years, for example, 6 on 4/25/2013. Photos by S. Cloutier are available. Reports shown on the map from Amherst, Northampton Florence, and Charlemont are all of 1 or 2 individuals, and Charlemont (1992) in particular needs re-confirmation.

In Montague at Turners Falls Airport, reports were made almost every year 1992-2010. Fairly high numbers were reported in the 1990’s through 2004 (e.g. 30, 5/9/1993, M. Fairbrother; 21, 5/9/1999, T. Gagnon; 15, 5/11/2004, T. Gagnon), but after 2004 there are hardly any reports of Frosted Elfins, despite timely visits. As of 2013, the only reports are of 1, 5/20/2008, S. Cloutier, photo; and 1, 4/21/2010, R. and S. Cloutier. The drastic decline of Frosted Elfin at this site seems due primarily to plant succession: second-growth forest was shading out the wild lupine at both sites, and at the airport deer browse was an additional factor damaging the host plant. In 2006 the main populations of the host plant were protected by deer fencing, and in 2007 a multi-year restoration project was begun to transplant lupine seedlings into various areas of the airport (Fairbrother 2009).

On the island of Martha’s Vineyard, Frosted Elfin is “inexplicably rare,” according to veteran observer Matt Pelikan, author of the local checklist (masslep post 5/15/2010; Pelikan 2002). Only 1-2 have been reported occasionally from the state forest in Edgartown, and from Katama plains (e.g. 2 on 5/22/2002 M Pelikan). The scarcity is surprising given the seemingly suitable habitat and abundant food plant (Baptisia). One factor may be the frequent frost damage to wild indigo in the cold “frost bottoms” in early spring. MBC has no reports from Nantucket, nor did the Atlas, and there are no valid historical records.

In eastern Massachusetts there are several well-known locations for Frosted Elfin where double-digit numbers have been counted, and other locations with smaller numbers. One of the best- monitored sites is Foxboro Lamson Road (Gavins Pond Municipal Water Authority property). The highest single-day counts are 127 on 6/1/2006, M. Champagne, 164 on 5/25/2002 M. Champagne and B. Cassie, 123 on 5/27/2012, and 78 on 5/27/2013 M. Champagne. Madeline Champagne's description of her monitoring, together with photographs of the site and Frosted Elfin ovipositing on wild indigo can be found in Champagne 2014. Some habitat restoration is being undertaken as mitigation for installation of a new water treatment plant in another part of the site.

Other important locations are North Andover Weir Hill (max 25 on 5/20/2009 S. Stichter et al; 32 on 5/2007 R. Hopping ); Plymouth Myles Standish SF ( max. 16 on 6/1/2008 E. Nielsen); North Dartmouth Noquochoke WMA (23 observed 5/19/1998 M. Mello); Acton/Concord Fort Pond Brook (max 17 on 5/16/2009 T. Whelan); Chelmsford Stage Road power line ( max. 8 on 5/16/2007 T. Whelan); ; Sherborn power line (max 6 on 5/14/2008 B Bowker); and Woburn Horn Pond Mountain (max 3 on 5/19/2003 B. Bowker).

On Cape Cod, Frosted Elfin has notably been found at Falmouth Crane WMA (est. 40 on 5/27/1998, M. Mello et al; 11 on 5/1/2013 A. Robb); Barnstable Marstons Mills Airport ( 3, 5/30/2011, J. Dwelly); and at Massachusetts Military Reservation in Bourne in 1997 and 1998, feeding on Baptisia (Mello 1998). There is also a report of a single from Wellfleet (4/20/2002, Bound Brook M. Lynch and S. Carroll), which is shown on Map 26 but requires further corroboration.

The comparative size of four colonies in eastern Massachusetts in 2004-5 can be gauged from the total numbers of adults observed throughout the flight period during Gene Albanese’s study (Albanese et al. 2007a). Total numbers ranged from 161 (2004) /183 (2005) at Gavins Pond Foxboro and 75 (2004)/ 90 (2005) at Crane WMA Falmouth, which were the larger colonies, compared to 10 (2004) /15(2005) at Noquochoke WMA Dartmouth. At Myles Standish SF, Albanese also observed 29 (2004)/16(2005), which were likely only one of several colonies at this site. Observations by M. Nelson of the state NHESP at Myles Standish over the past ten years indicate that there are probably a number of small semi-isolated colonies comprising what is a large meta-population (M. Nelson, pers com. 2/25/2011).

The Lamson Road site in Foxboro is owned and managed by a municipal water authority. This population of Baptisia-feeding Frosted Elfins has been monitored every year since 1999, primarily by Madeline Champagne. The yearly maximum single-day counts have fluctuated from a low of 2 in 2000 to a high of 164 in 2002. From 2001 through 2007 the population seemed to flourish, with high counts ranging between 73 and 127, except for 29 in 2003. Then in 2008 there was an inexplicable drop. The first sighting came late, and only 7 were seen at the peak of the flight. By 2009 and 2010 the population had recovered, with maxima of 23 on 5/25/2009, 39 on 5/24/2010, and 78 on 5/27/2013. The drop in 2008 is still unexplained, but may have been due to a parasite. The semi-open habitat here has maintained itself for some time with no mowing or brush cutting. However, aggressive sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina ) is a problem.

Weir Hill, a Trustees of Reservations restoration site in North Andover, typifies a Baptisia-feeding Frosted Elfin population inhabiting a thin soil, hilltop ‘barrens,’ historically kept semi-open by fire and grazing (Hopping 2009). Like Horn Pond Mountain to the south, such areas have come to function as refuges for uncommon flora and fauna as surrounding lowlands were developed. At Weir Hill the Trustees conducted rotational prescribed burns in 2008 and 2009, successfully restoring habitat for many plants and lepidoptera, including Baptisia tinctoria and the Frosted Elfin. Double-digit numbers of Frosted Elfins were found in 2009 and 2010.

Broods and Flight Periods

Like all of our elfins, Frosted Elfin is univoltine, with a single flight period from late April to the end of June. Peak flight numbers are in the last three weeks of May ( http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp ).

Earliest Sightings: For the 23 years 1991-2013, the six earliest "first sighting" dates are 4/6/2012 Westfield Barnes Airport, T. Gagnon; 4/8/2010 North Andover Weir Hill, H. Hoople and R. Hopping; 4/11/2004 Montague Turners Falls, D. Case; 4/24/2009 North Andover Weir Hill H. Hoople; 4/26/2009 Plymouth Myles Standish E. Nielsen; and 4/27/2006 Foxborough Lamson Road, M. Champagne. Ten out of 23 "first sightings" are in April, the rest are in May. The exceptionally warm winter and spring of 2012 accounted for the new early sight record was set that year.

Latest Sightings: In the 23 years under review, the three latest "last sighting" dates are 6/29/2003 Plymouth Myles Standish T. Murray; 6/24/2007 Woburn Horn Pond Mountain S. Moore; and 6/21/2009 Foxborough Lamson Road M. Champagne. No sightings have been reported in July in any year.

There is no usable information from Scudder on flight dates in the 19th century.

Flight Time Advancement: Unlike Brown Elfin and Eastern Pine Elfin, Frosted Elfin did not advance its flight time to any great extent during the years 1986-2009, according to a 2012 study done at Boston University using MBC and Atlas data (Polgar, Primack, et al. 2013; graph courtesy of Caroline Polgar).

Graph 26: Change in the first 20% of all Frosted Elfin sightings, 1986-2009

The trend in the first twenty percent of all sightings in these years is a bit earlier, but is not statistically significant ( p=0.128). However, when 2010-2012 data are added, Frosted Elfin is found to have significant flight advancement (Williams et al. 2014). Like most elfins studied, Frosted Elfin shows a statistically significant response of flight time to temperature variations in the two months prior to emergence (March, April), varying its flight time according to temperature. This responsiveness to temperature is an adaptive trait.

Outlook

Frosted Elfin has a wide range across eastern North America, including southeastern states. But its range has contracted historically, and everywhere populations are localised in sensitive habitats. The species is historic or extirpated in Ontario, Maine and Illinois, and is declining in most areas (NatureServe 2010). It is often confined to remnant habitats along powerlines, airports, railroads, and old gravel pits, dependent on almost fortuitous management. The NatureServe ranking is S2S3 (imperiled) in MA and CT and NJ; S1 (critically imperiled) in NH, RI, NY and PA.

Frosted Elfin was not found in the recent Maine Butterfly Survey (MBS 2011) and is presumed extirpated there; the 2002-2006 Vermont Butterfly Survey found it in only 1 atlas block. In Connecticut Frosted Elfin is state-listed as Threatened. The 1995-99 Atlas found only 10 project vouchers compared to 32 preproject vouchers, and concluded that this species had declined due to “loss of barrens and other open early successional habitats, and deer browsing.”

In Massachusetts Frosted Elfin is listed as of Special Concern by the state Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP), and observations should be reported at (http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/nhesp/species_info/pdf/electronic_animal_form.pdf ). Collecting without a state-issued permit is prohibited. According to Michael Nelson of the NHESP, most colonies in the state continue to be threatened by habitat loss and lack of the management necessary to maintain them over the long term (pers. com. 2/25/2011). Because this species is state-listed, any development projects in its mapped “priority habitat” must be reviewed by NHESP. Impacts to habitat must be minimized, and any substantial impact requires mitigation. Projects continue to be proposed within Frosted Elfin habitat.

Frosted Elfin appears to be benefiting from climate warming in Massachusetts (Table 6), in contrast to Hoary Elfin, an equally specialized species which has a more northerly range and may be negatively impacted.

© Sharon Stichter 2011, 2012, 2013

page updated 4-22-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS