ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS

The Butterflies of Massachusetts

84 Common Sootywing Pholisora catullus (Fabricius, 1793)

Jet-black with sparkling white dots, the handsome Common Sootywing may have been quite familiar to the earliest human agriculturalists in North America. Its host plants, amaranths and chenopodiums, naturally thrive in disturbed areas around human settlements. Chenopodium, in fact, was domesticated by Native Americans as a food crop.

This species was one of the first New World butterflies to be described and named; it was figured by John Abbot in Georgia in the late 1700s. Scudder reports Common Sootywing as "not uncommon" in Massachusetts and Connecticut at the end of the 19th century, and it was actually very common in the lower Connecticut River valley. Many collectors had found it in Springfield, Northampton, Mt. Tom, and South Hadley (1899: 1523).

Photo: Northampton community gardens, F. Model, August 21, 2006

In 1874 Mr. H. W. Parker wrote an article in Psyche, the journal of the nascent Cambridge Entomological Society, entitled “Novelties in Amherst, Mass.” Among the “novelties” was Pholisora catullus; Parker collected a male in June, and also found the species “not rare” on and after July 30. Two of his 7/31/1874 specimens are still in the Boston University collection today. In 1883 F. H. Sprague found many Common Sootywings in West Springfield (seven 8/9/1883 specimens at MCZ, one at BU); he also found it that year on Mt. Tom and in Hadley (MCZ specimens). Evidently Sprague had not found it around Boston, his usual collecting area (Sprague 1879; he finally found it in Quincy in 1940, specimens in MCZ)). But Scudder had collected it in Boston, and Hambly in Middleboro, so it did occur in eastern Massachusetts, but was less common than in the Connecticut River valley (Maynard (1886).

Common Sootywing must have been lightly present along river banks and around Indian settlements prior to the arrival of Europeans, and very likely increased around colonial and post-colonial habitations and urbanizing areas 1600-1850 (Table 1). It seems likely to have increased or held steady through the industrializing years of 1850-1950, but does not seem to have been widely collected or reported. By 1934 Farquhar can add only the town of Salem to Scudder’s list of Massachusetts locations. In 1942 Nabokov, and in 1950 D. T. McCabe, collected it in Wellesley, and in 1957 C. G. Oliver collected it in Concord (specimens at Yale and MCZ). In the 1970's, W. D. Winter collected it in Medfield, Westwood and Millis (MCZ).

Today Common Sootywing is more common south of Massachusetts, for example in Connecticut (“common” CBA Checklist; O’Donnell et al.), New York (“very common around New York City, less so upstate” Shapiro 1974), and New Jersey (“fairly common, occasionally abundant” Gochfeld and Burger 1997). Massachusetts is in Common Sootywing’s secondary range, rather than its primary (Opler and Krizek 1984), but the species is probably increasing here. It is rare in both Maine and Vermont (see below), and therefore Massachusetts is effectively the northern limit of its range in eastern North America.

Host Plants and Habitat

Common Sootywing’s host plants are annuals in the Chenopod and Amaranth families: primarily Chenopodium album, ambrosioides, berlandieri and others (lamb’s quarters; goosefoot), and Amaranthus caudatus, retroflexus, spinosus, hybridus, and albus (pigweed) (Scott 1986). Except for C. album, which is naturalized from Europe, most Amaranths and Chenopods are native to the New World. They were probably introduced into New England from further south (Sorrie and Somers 1999), probably by Native Americans. But today they are widespread (McGee and Ahles 1999).

The 1990-95 Connecticut Atlas found Common Sootywing eggs or larvae on two plants, one native Amaranthus retroflexus, and one introduced, Chenopodium album. Thus Common Sootywing is among those species which have adopted a non-native host in addition to its several native hosts (Table 3, Switchers). In Massachusetts photographer Sam Jaffe found Common Sootywing on either amaranth or chenopodium in 2009 in the Blue Hills in Milton; other MBC members report it using pigweed or lamb’s quarters in their gardens.

Common Sootywing is at home in open areas created by human disturbance, such as vacant lots, weedy backyards, landfills and edges of croplands and pastures. Today, it is not usually found in natural settings. A number of sources (Opler and Krizek 1984; Cech 2004) mention sandy river banks and sand plains as the original habitat, because chenopodium often colonizes river sandplains after floods. Interestingly, these were also the areas also favored by Native Americans for their encampments.

Native Americans in the Late Woodland period prior to European arrival in Massachusetts gathered various chenopodiums and ground the seeds into a meal. Charred remains of C. incanum and C. berlandieri have been found in small quantities in hearth excavations in New England in time periods prior to the advent of maize cultivation (1300-1600). Chenopodium was probably simply gathered here, judging from its morphology, rather than cultivated, although it was a domesticated cultigen among other Native American groups who lived to the south and west, in Pennslyvania and the Great Lakes area. Still, even the “conditional sedentism” of many New England coastal and riverine Native American groups disturbed the land somewhat, and chenopodium was clearly present around Indian encampments, along with amaranth and other open area “weedy” plants such as composites, ragweed, and nettles ( Bragdon 1996: 39; 55-71; Bernstein 1999; George and Dewar, 1999).

Relative Abundance Today

The 1986-90 MAS Atlas found this species in only 70 out of 723 blocs, which would place it firmly in the “Uncommon” category. MBC sight records 2000-2007 place it similarly at the bottom of the “Uncommon-to-Common” category, relative to other species (Table 5). It is most definitely not a “Common” species, like American Copper or Little Wood Satyr. As the joke goes, it is the “Not-so-Common Sootywing.”

An upward trend in sightings of Common Sootywing has been demonstrated in list-length analysis of 1992-2010 MBC data: the species showed a statistically significant 55.5% increase over these years (Breed, Stichter, Crone 2012). MBC sightings per total trip reports 1992-2009 also show a generally upward trend through 2005 (Chart 84), then a decline after that. Linear regression of these data (R²=0.496) show an overall upward trend over these years. However, human search effort is not well captured in total trip reports, partly because of the advent of the Northampton NABA Count in 2001.

Chart 84: MBC Sightings per Total Trip Reports, 1992-2009

The readings after the year 2000 are strongly affected by the beginning of the Northampton NABA Count in 2001. The high readings in 2003, 2004 and 2005 and 2007 reflect relatively large totals of 77, 62, and 106 Common Sootywings found on that Count in those years. Northampton Count totals were down to 41 in 2006, and have fluctuated in a lower range 2008-2013, with 46 in 2008, 0 in 2009, 14 in 2010, 32 in 2011, 26 in 2012, and 34 in 2013. Human effort on this count has not fluctuated that much from year to year.

State Distribution and Locations

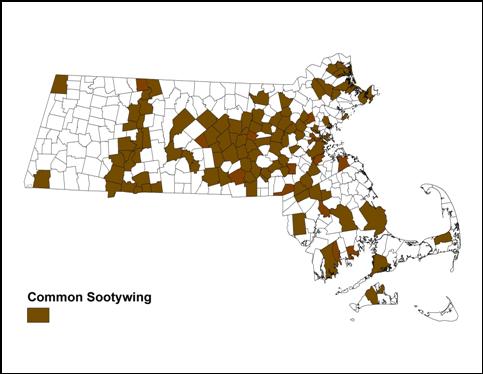

Map 84: BOM-MBC Sightings by Town, 1992-2013

Common Sootywing has been reported from 108 out of a possible 351 towns in Massachusetts (Map 84).

This species is well-distributed across the state, except for Berkshire County, where it is rare. There are reports from only two towns in this county Williamstown (2 reports) and Sheffield (5 reports). Singles were reported for four years in the 1990's on the South Berkshire NABA Count; the most recent report is 1, Sheffield Bartholomew's Cobble, 7/8/2012, B. Benner. The Williamstown reports are 1 on 6/5/1994 and 1 on 5/28/1998, P. Weatherbee.

Common Sootywing remains particularly strong in the Connecticut River valley, just as it was in Scudder's day. This might be expected from the species' river valley origins. There are reports from towns north to south all along the river. The high numbers reported for many years from the Northampton NABA Count (max. 106 on 7/22/2007) far outstrip the numbers found on any other NABA Counts.

Common Sootywing is also well concentrated in central Massachusetts, both north and south of Worcester. Groton is the furthest north sighting in this area; there are no reports from towns along the New Hampshire border.

Oddly, Common Sootywing is uncommon on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. Mello and Hansen (2004: 58) report that it is “uncommon” on Cape Cod, and believe it has declined generally in southeastern Massachusetts, perhaps due to herbicides or pesticides. Falmouth and Brewster are the only two towns on the Cape from which BOM-MBC has reports, and these are few reports of few individuals. The 1986-90 MAS Atlas also found it uncommon on Cape Cod. There are likewise only a few reports from Martha’s Vineyard, and the Vineyard checklist ranks it as “Uncommon” (Pelikan 2000). Neither the Atlas nor BOM-MBC has any reports from Nantucket.

On Cape Ann, the 1986-90 Atlas had also reported Common Sootywing as uncommon, but BOM-MBC has several reports from Gloucester, Marblehead and Saugus, and many from other north shore towns such as Ipswich, Topsfield and Newbury. The furthest north towns are Newburyport and West Newbury.

Common Sootywing is found on many of the NABA Counts due to its flight time. Aside from Northampton, it is consistently reported on the Concord Count (max. 24 on 7/10/1999) and the Blackstone Valley Count (max 13 on 7/16/2005). A Boston NABA Count was held once, on 7/23/2006, and turned up 19 Common Sootywings. The infrequently-held Lower Pioneer Count, based in Springfield, reported 13 on 7/15/1995.

Common Sootywing is usually observed in small numbers of less than five at a site. Locations which have proved particularly productive 1991-2013 are Boston/Roxbury Millennium Park, max 10 on 5/30/2009 E. Nielsen; Bolton/Lancaster Bolton Flats, max. 6 on 5/30/1999 B. Walker; Carlisle Great Brook Farm, 6 on 8/26/1999 T. Dodd; Concord Great Meadows NWR, 4 on 5/8/1999, B. Cassie; Dartmouth Allens Neck, 5 on 7/29/2007, E. Nielsen; Grafton Dauphinais Park, max. 13 on 5/29/2011, D. Price et al.; Hadley, 20 on 7/21/2013, B. Benner; Lexington Dunback Meadows, 3 on 7/19/2003, T. Whelan; Newbury Martin Burns WMA, 17 on 7/23/2011, J. Stichter (ph.); Northampton community gardens, max. 26 on 8/22/2004, B. Benner; Springfield Forest Park, 5 on 8/5/2000, T. Gagnon; Stow Delaney WMA max. 28 on 6/2/2000 B. Walker et al.; Upton, 5 on 7/14/2012, T. Dodd; Wayland community gardens, max. 10 on 8/24/1999 B. Cassie; Westborough Heirloom Harvest comm. gardens, 9 on 7/17/2013, G. Kessler.

Broods and Flight Time

Common Sootywing has two to three broods throughout its large Canada-to-Florida-to-Mexico range, and also two or three in Massachusetts. According to MBC 1993-2008 flight records (http://www.naba.org/chapters/nabambc/flight-dates-chart.asp), the first brood flies from about late April to mid-June, and the second peaks in mid- July, but continues flying into September. The long period covered by the second flight, and a cluster of sightings in late August/early September, suggest that there are three broods here in some locations.

Three broods were apparent at one continuously monitored vegetable garden in Newbury, Massachusetts in 2010. Fresh individuals were observed, after gaps, on 5/25/2010, 7/4/2010, and 8/26/2010 (S. Stichter). At Northampton community gardens, which is frequently visited by MBC members, three broods were also suggested in at least one year, 2007, when Common Sootywings were first seen on 5/3 (3, B. Volkle), then again from 7/24 through 8/11/2007, and again from 9/3 through 9/18/2007 (various observers).

Earliest sightings: In the 23 years of BOM-MBC records 1991-2013, the seven earliest "first sightings" are 4/30/1998 Northampton Florence, T. Gagnon; 5/1/2010 Ware, B. Klassanos; 5/8/2006 Boston Nature Center, A. Birch; 5/8/2004 West Brookfield, M. Lynch and S. Carroll; 5/8/1999 Concord Great Meadows, B. Cassie; 5/10/2003 Plymouth Myles Standish SF, T. Murray; 5/10/2002 Northbridge, R. Hildreth. The Atlas first sighting date was similar: 5/10/1987 Braintree, R. Abrams.

Scudder wrote that the earliest flight of Common Sootywing “appears toward the middle of May,” citing May 12 for Connecticut (1889: 1526). Today's first flight would appear to be occurring a bit earlier.

Latest sightings: In the same 23 years of records, the four latest "last sightings" are 9/21/2002 Marblehead, K. Haviland; 9/20/2010 Stow Delaney S. Moore; 9/20/2003 Northampton community gardens, Nielsen/Gagnon/Murray; and 9/19/2006 Newbury, S. Stichter.

Since 1999, all last sightings have been in September. A century ago Scudder wrote that the second brood “appears very late in July and probably flies until September (1889: 1526).” The late flight date does not seem much changed since then.

Outlook

One might think we need not worry about this butterfly, because of its liking for disturbed habitats. Yet there are many areas of Massachusetts where this species is very scarce or not found at all, either because of lack of habitat or cold intolerance. The butterfly overwinters as an unfed larva, and pupates in the spring.

NatureServe has assigned no rank to Common Sootywing in Massachusetts or other New England states outside of Connecticut. But it is not a common butterfly, and Massachusetts is at the northern edge of its range. The 1995-2010 Maine Butterfly Survey found Common Sootywing in only one township in extreme southern Maine (MBS 2/2014). The 2002-2007 Vermont Butterfly Survey (VBS) found in “extremely rare” in Vermont and ranked it S1. It was found only in the southern part of that state.

If climate warming means milder winters, that might lead to an increase in Common Sootywing’s numbers. But if it means colder, snowier winters, that outcome is uncertain. Common Sootywing is therefore not listed on Table 6. More research needs to be done on the response of this species to temperature variations.

© Sharon Stichter , 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

page updated 2-17-2014

ABOUT BOM SPECIES LIST BUTTERFLY HISTORY PIONEER LEPIDOPTERISTS METHODS